Guest Blog - You Can Go Home Again

/by Sierra Gitlin, Administrative Assistant

Spending your days sifting through old photographs and extensive genealogies, as we do at the Museum of Old Newbury, can make you question your bona fides as a Newburyporter. This small city, like many, I suspect, has a strong sense of the importance of its storied families. Familiar surnames repeat themselves on street signs, landmarks, memorials, buildings, and tombstones, and many descendants of the first European settlers who landed on the Parker River in 1635 still live here. How does someone like me then, who measures my time here in just a couple of interrupted decades, not in unbroken centuries or generations, come to call Newburyport home?

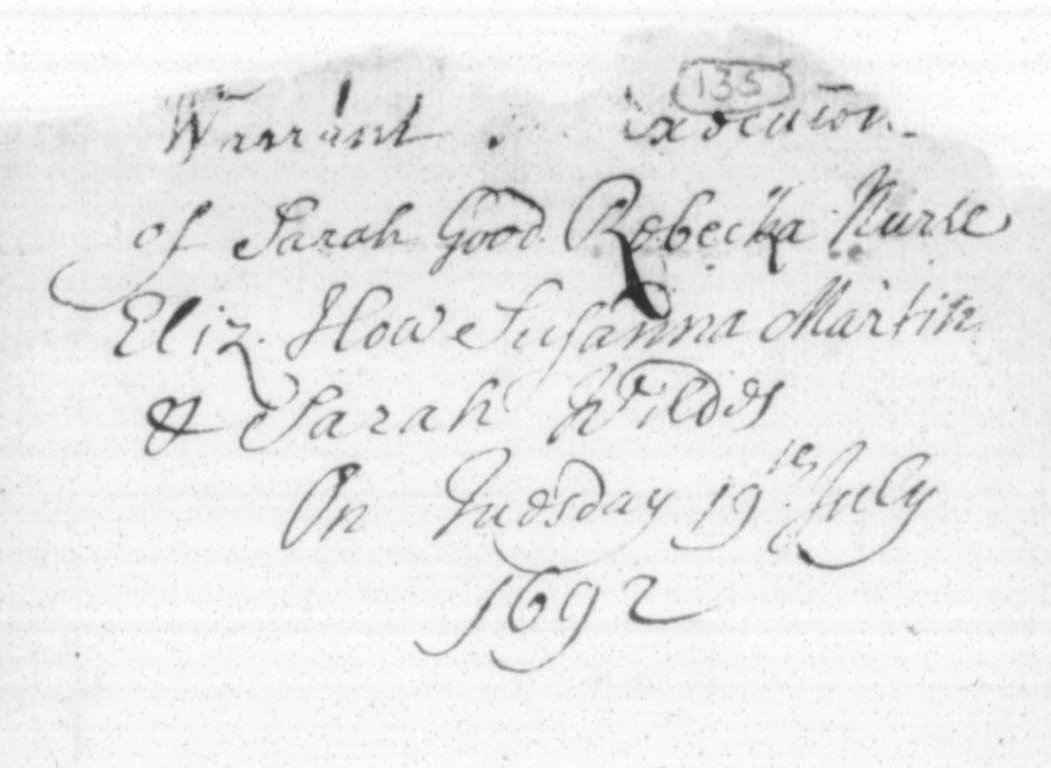

Market Square circa 1979

My earliest memories are of my own feet slapping along the bricks of Market Square, chasing pigeons on Inn Street to the sandy tot lot, breakfast at Fowle’s, preschool in the YMCA basement, and what seemed like hours sitting in Ferlita’s while my dad played (dominated, to hear him tell it) the Missile Command arcade game. My parents met at the Grog in 1974. Mom was a waitress and dad was in the band that was playing that night.

The Grog - still in business today in 2023!

She had moved here shortly after graduating with a fine arts degree from Boston University, because Newburyport was, at that time, an affordable place to live with a thriving arts scene. Her apartment on Dalton St. was $90 a month. My dad quickly fell in love, with my mother and with this seaside town, and relocated from Vermont where he had been spending his early 20s skiing and playing in a rock and roll band. When I was born in 1978, we lived at 48 Milk Street.

The South End was a different place then - our house was broken into often, my mom once had to buy her stolen wedding ring back from a pawn shop downtown. Eventually we moved just over the border to Newton NH, where I did most of my schooling, my parents attracted to the quiet, privacy, and breathing-room of the country. But Newton had no grocery store, no bank, barely a gas station at that time, so we would come to Newburyport several times a week, and always on Saturday mornings, to shop, do errands, see friends, and have breakfast at Fowle’s. As soon as I got my driver’s license, I’d come hang out in Newburyport, back on Inn Street. I was too old and too cool to chase pigeons, never too old for a jaunt to Fowle’s for hot chocolate, and just old enough to be making calls from the wooden phone booth in the front corner. But I was always a bit of an outsider, since I didn’t live here anymore, or go to school here. I was from two places - these brick sidewalks, and the woods of NH.

Looking up Inn Street from the fountain. Note the balloon seller.

Despite living elsewhere from the ages of 6 to 24, my early years in Newburyport, and my family’s weekly, almost ritualistic, return throughout my childhood and teen years made it feel like my true home. Once I grew up and got married, it was the only place I could imagine living and raising kids. Luckily my husband was amenable, and we were able to buy a house back in the South End, just steps from where I started my life. My kids were born at Anna Jaques Hospital, and I pushed them in strollers to the new playground on Inn St, where THEY took their turn chasing the pigeons. We had many breakfasts at Fowle’s when they were very young, just before it closed and changed, and changed again. I was able to walk them downtown to preschool at Newburyport Montessori, run by the same remarkable women who ran Spring Street School, where my mom had walked my brother and me 30 years earlier.

A last photo of Fowle's before it closed in 2012.

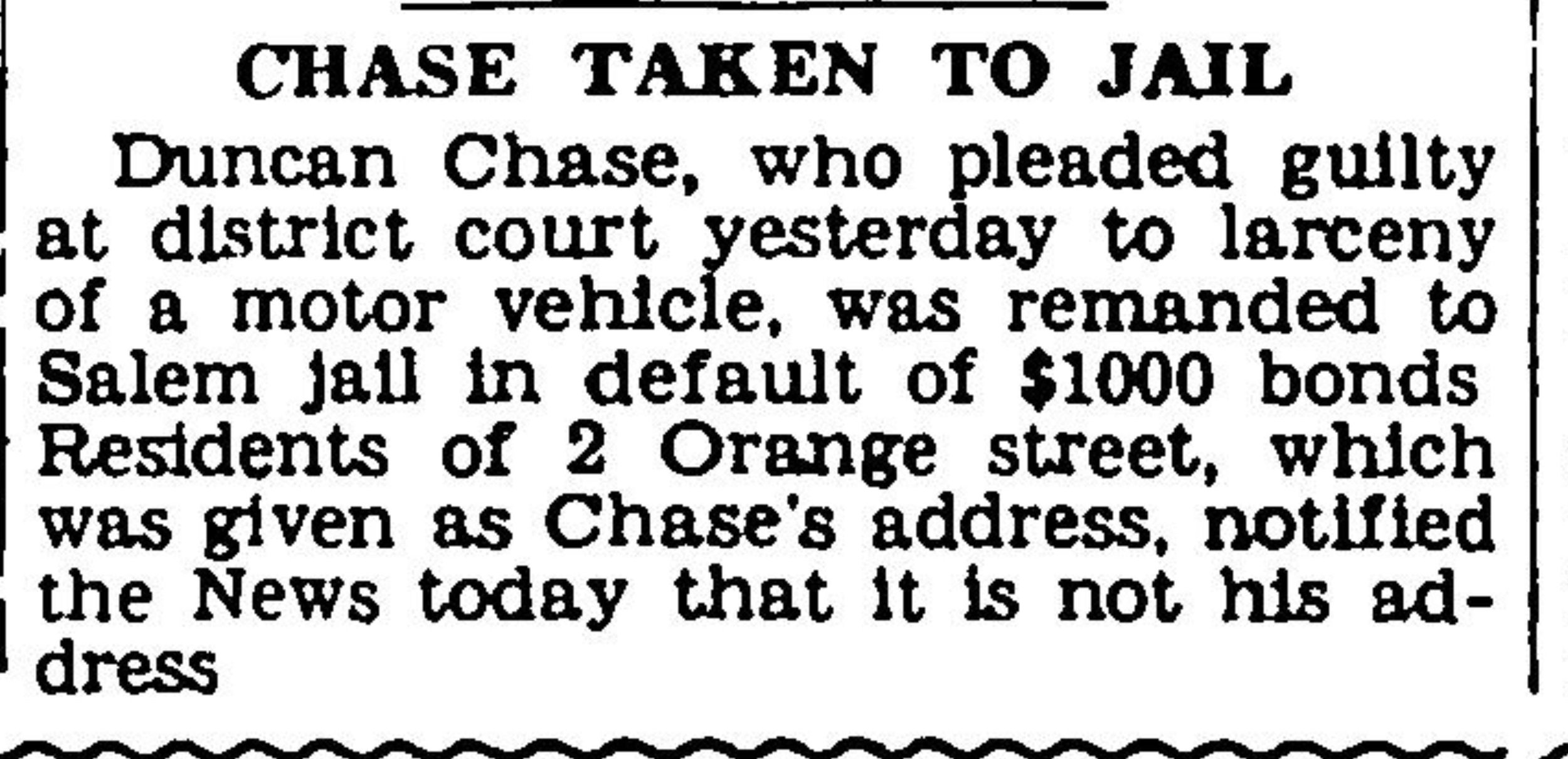

I've now lived here as an adult longer than I lived in New Hampshire or anyplace else, and though my genealogy has no ties to any early settlers at all - my ancestors immigrated from Ukraine, Europe, and the UK around the turn of the 20th century - Newburyport is my home, and my children’s home. My life’s seemingly wandering path has actually led me in a circle. I can see my first house on Milk Street from my bedroom window here on Orange Street, where I’ve been lucky enough to call the purple, turreted Queen Anne Victorian “Moody House” my home for the past 16 years. I am rooted here not by birth, but by choice, by luck, sometimes I think even by destiny, given how close to my starting place I now live. Once you've spent time in Newburyport, it’s impossible not to feel a deep connection to this spectacular bit of coastline and riverbank and marsh and woods. Working at the Museum of Old Newbury, learning more than I knew there was to know about Newburyport and the families and individuals who built it, that connection has only grown. It sounds like a cliché, but home really is where the heart is, and whether your family has been here for three years, three decades, or three centuries, it’s easy to be madly in love with the beauty and history of this remarkable city.