Where's Waldo? Why Newburyport, of course.

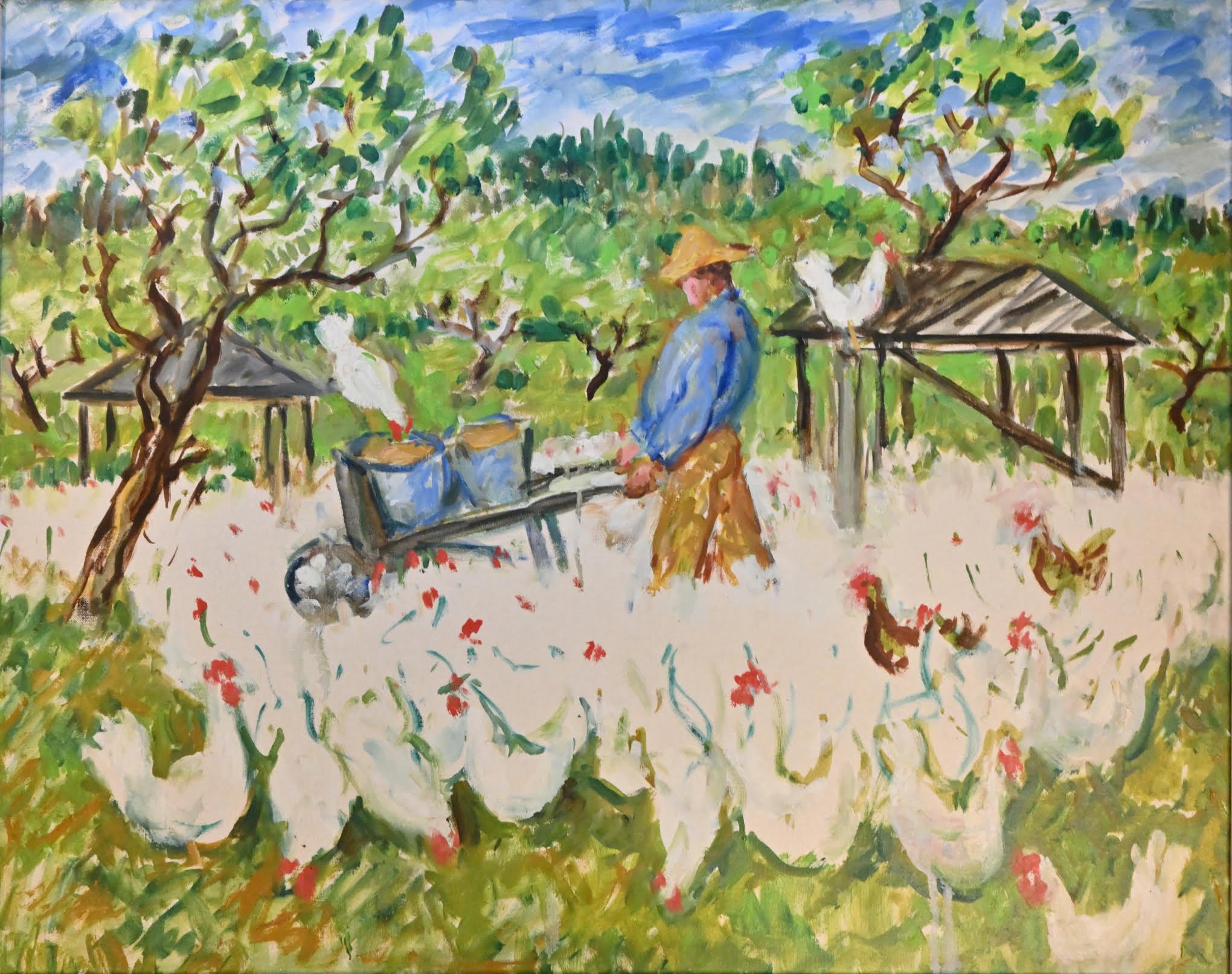

Painting by Waldo Peirce, gift to Paul Plourde, oil on canvas, 1969

a blog by Bethany Groff Dorau

I fall in love with dead people about a dozen times a day, by which I mean that some turn of phrase, some item on an inventory, some bit of a recollection or an object saved, a dusty bit of something is added to a keepsake box in my heart. It’s strange, but that’s how it feels – like love, like finding an essential bit of humanity and understanding something about what it means to be here right now, alive in this moment.

A few months ago, someone challenged my description of an ancestor as one of my “dead friends.” It is a bit of a disingenuous turn of phrase, of course, as a living friendship is mutual and ever-changing, but it feels true in that I think about many of these people the same way I think about my living friends. Who did they know? What would they think about the state of the world? How do their lives and passions connect with other friends of mine?

It will come as little surprise, then, that today I am in love with Waldo Peirce. He knows other friends of mine, living and dead, and memories of him are all around this community. He is a new friend, and I think the story of our meeting bears repeating.

Portrait of Waldo Peirce by George Bellows (1920), image courtesy de Young Museum

Several weeks ago, a woman contacted the museum to ask if we were interested in a painting by a local artist. We said yes, somewhat hesitantly, because “are you interested” often means “Would you be interested in buying?” Imagine our delight when this woman and her husband came to the museum with a large painting of a man with a flock of chickens, and reams of background information – letters, bills, exhibition catalogs, things they had found in the yard of their house, where Waldo Peirce once lived. They were moving out of state, they said. They loved this painting and they wanted it to stay in Newburyport. They had received the painting from the previous owner of the house, whose death from COVID rendered their gift even more poignant and meaningful.

And it was a gift. They understood its monetary value and chose to honor their few years in the community by giving the painting and its associated materials to the Museum of Old Newbury, and, by extension, to all of us. This, to me, is always a bit of a shock, accompanied by deep gratitude. In a world of people who grab and hoard, I am still in awe of the givers, who understand what it means to leave something important in trust to a community.

The painting is temporarily displayed in the office, and so when one of our board members came for an event, she stopped and laughed. “He worked on Inn Street before everything was torn down,” she said. “We used to try to sneak a peek and see if Mr. Peirce had any naked people in his studio.” And this is what happens to me in a moment like this. This board member, who I know well, is suddenly a girl with an ice cream cone, and Inn Street is a warren of artists, shops, and alleys, and Waldo Peirce is alive again and be-smocked, a dripping brush held in his mouth, as he considers whether to paint clothing on a reclining model, much to the delight of Newburyport’s roaming young folks.

Inn Street, c. 1960’s. The Plourde barber shop and Waldo Peirce’s studio are out of frame along the left side of the street.

Waldo Peirce, though related to Newbury’s early Peirce family, grew up in Maine. It is beyond my power to do justice to his remarkable life, so I will quote a 2018 article in the Portland Monthly magazine. “Rabelaisian, bawdy, witty, robust, wild, lusty, protean, lecherous, luscious, the kind of man Ernest Hemingway wished he could be, Waldo Peirce (1884-1970)…devoured life.” Waldo Peirce was a Harvard football player, a competitive swimmer, a voracious lover, and by all accounts, a devoted father and grandfather. But it was his personal courage, evidenced in his role as volunteer ambulance driver for the American Field Service that made him my friend. You see, I know them, the Harvard and Yale boys who thought the Great War would be a grand adventure. I know them, in part, because for 21 years I had a role in the management of Beauport, the home of Henry Davis Sleeper, who was one of the founders of the American Field Service with his friend and neighbor A. Piatt Andrew. Sleeper, Peirce, and Andrew were all awarded the Croix de Guerre for conspicuous bravery by the French government. Waldo Peirce’s portrait of A. Piatt Andrew, given to their mutual friend Isabella Stewart Gardner, is a striking memento to all involved in the service.

A Piatt Andrew by Waldo Peirce, c. 1918

Of course, the most famous ambulance driver in World War I is Ernest Hemmingway, and it was the shared wartime experiences of these two men that forged an intimate friendship. In 1927, the pair ran with the bulls in Pamplona, and for the rest of their lives, both inspired the art of the other.

Peirce and Hemingway in 1959. Image courtesy Tucson Sun.

Waldo Peirce lived in Newburyport off and on for decades, and the first gift of this painting was made from the artist to Paul H. S. Plourde, Peirce’s barber, whose shop was near his studio on Inn Street. 53 years later, it walked through my door.

I think of how many times I have met someone and found myself using the shorthand “I’ve heard so much about you,” a way of saying, “I know you a bit already.” This is how I feel about Waldo Peirce. I know him a bit already. How could you not, with quotes like this? From his nephew, “I remember a musty tobacco smell coming from a huge, gentle, and confident man with an impressively grizzly beard. He had a deep, gruff and beautiful voice,” and from an old friend, Vincent Hartgen, “Waldo was a pretty good artist, but he was truly a great man.”

The Barber Shop, 1949, oil on canvas, by Waldo Peirce.

For me, the beard is key to his allure, as is the height – he was over 6 feet tall, but it was his writing, not his art, that I will tuck into the keepsake box in my heart. Here is his homage to his friend Richard Hall (1894-1915), published shortly after Hall’s death while driving an ambulance in France.

Gentlemen at home, you who tremble with concerns at overrun putts, who bristle at your partner's play at auction, who grow hoarse at football games, know that among you was one who played for greater goals--the lives of other men.

There in the small hours of Christmas morning, where mountain fought mountain, on that hard bitten pass under the pines of the Vosgian steeps, there fell a very modest and valiant gentleman.

-Friends of France, 1916

Waldo Peirce sketching on the side of an ambulance, circa 1915-1916. Courtesy of the Archives of the American Field Service and AFS Intercultural Programs (AFS Archives.)

Imagine my surprise, and then no surprise at all, when one of the artifacts from Waldo Peirce’s Newburyport home turned out to be a small piece of type with the name of Harold DeCourcy, a fellow ambulance driver in France. Did it fall from the pocket of his old friend when he came to visit Peirce decades later in Newburyport? Was it a memento of their time together? We will likely never know. What I do know, for certain, is that the gift of that painting ripples outward into my life, and that of the museum and the community. It is a powerful reminder of how much is yet to be learned, and how many dead friends we have yet to meet.

Found while metal detecting at the Waldo Peirce home. Harold DeCourcy was a fellow ambulance driver in WWI.

Do you have images and/or memories of Waldo Peirce? Please share them with the Museum, as it will enrich our understanding of this artist's time in Newburyport. Email info@newburyhistory.org.