Courage, Cowardice, China, and Cushing

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

On June 17, 1843, Caleb Cushing went to dinner at Faneuil Hall. It had been a bruising year, and Cushing had barely managed to snatch victory from the jaws of humiliating defeat.

Cushing, then a Congressman from Massachusetts, was becoming known for his inconsistency and willingness to vote both for and against bills and change political parties as he saw an advantage. He had been nominated by President John Tyler to serve as Secretary of the Treasury, but the Senate refused to confirm him. He was nominated three times in one day, and as many times rejected. President Tyler, whose long relationship with Cushing deserves more than a passing line here, then appointed his friend to lead a delegation to China to secure a trade treaty. It was an opportunity for Cushing to rebuild his reputation, and he took full advantage of the months between his appointment and his departure to talk up the importance of his mission. Hence the dinner at Faneuil Hall, at which both President Tyler and Daniel Webster were also guests.

The occasion was the dedication of the Bunker Hill Monument, memorializing the battle where Cushing's fellow Newburyporter, Samuel Gerrish, had ignominiously contributed to the American defeat.

This seems to be a theme in my life and work, dear reader. Begin the week thinking about Caleb Cushing and the China Trade as we plan the China Trade Conference on October 28 (you should come, of course - click here for more), and then take what seems to be a completely left turn to write about Samuel Gerrish. Then, oh serendipity, find Cushing doing what you could not have imagined could be done - linking, as only a career politician could - the Battle of Bunker Hill and trade with China. I'll let Cushing take it from here...

Not merely relating to the conflict of 1775; not to the ever-remembered victory which ushered in our national existence ; nor to the scene which was the glorious dawn of our existence ; nor to the mere military triumphs, glorious as they were in that battle-day which is first among our annals of the war. I...see now, that peace has her triumphs, no less than more brilliant war...

I have myself been honored with a commission of peace, and am entrusted with the duty of bringing nearer together, if possible, the civilization of the old and new worlds - the Asiatic, European and American continents.

For though, of old, it was from the East that civilization and learning dawned upon the civilized world, yet now the refluent tide of letters - knowledge, was rolled back from the West to the East, and we have become the teachers of our teachers."

Cushing then turned dramatically to President Tyler, addressing him directly. "I go to China, sir, if I may so express myself, in behalf of civilization, and that, if possible, the doors of three hundred millions of Asiatic laborers may be opened to America. And if there is to be there another Bunker Hill monument, may it not be to commemorate the triumph of power over people, but the accumulating glory of peaceful arts, and civilized life."

Cushing's vision of China as an ancient center of learning, now fallen so far behind the United States that "we have become the teachers of our teachers", is patronizing at best. There are many other elements of Cushing's vision of his mission "on behalf of civilization" that are deeply problematic. Closer to the truth was his telling line about the "three hundred million" who would be "opened to America". Whatever else Cushing sought to achieve, his mission was clear. Through threat and flattery, coercion and conviction, he was to secure for the United States a treaty that would open up Chinese markets to American goods and vice versa. If he were to fail, England would have a critical advantage over the United States in international trade.

If the subsequent journey to China and the 1844 Treaty of Wanghia interest you, come to the conference, where Eric Jay Dolin and Dane Morrison will describe its impact far more eloquently than I ever could.

When America First Met China by Eric Jay Dolin, is an excellent overview of the early years of the China Trade. Dolin is a featured speaker at the Newburyport and the China Trade Conference on October 28.

Memory and meaning are my obsession. The Battle of Bunker Hill was, to Cushing, and many others, "the glorious dawn of our existence" as a nation, and there is some truth to that. Though the Provincial troops were defeated that day, they inflicted horrific casualties on the British troops, killing or wounding some thousand of them, out of a force of 2400. It was a watershed event, worthy of remembrance. Cushing employed the memory of Bunker Hill to argue that peace, and, self-servingly, diplomacy and trade were the new path to American victory. His speech was widely quoted in the publications of peace leagues across the country. It is worth mentioning, however, that Cushing arrived in China in February 1844 in a convoy of warships.

1848 View of Bunker Hill Monument, Charlestown, built 1824-43, Solomon Willard architect. Digital Commonwealth

Any historical event is unknowable, in a way. It is experienced differently by every person, whose perspective, experience, bias, and status influence what meaning they make of it. Facts can be secured, carved in stone, but meaning is endlessly shifting. Samuel Gerrish hiding behind a haystack, the blood and chaos and smoke of the fight before him, may be a coward, or a realist, or he may have been suffering the traumatic effects of decades of bloody military service. Several later writers argued that he had been a scapegoat for widespread failures of leadership at the battle. Caleb Cushing was certainly not representing his experience as he prepared to sail for China.

It is easy to distill a whole life to one line. The title of the earlier piece does just that. "Cowardly Colonel of Bunker Hill" is not the sum of Samuel Gerrish's life, though there is ample evidence that this is an accurate description of his observed behavior. Nor is Caleb Cushing's celebrated negotiation of the Treaty of Wanghia in 1844 an accurate summation of the life and work of a very complex man whose failure to speak and work against slavery may have been typical of his time, but still stands out as a failure of conviction. Today I am mulling over the meaning of courage, how it shifts in one's life, how I have been courageous or cowardly, and at times both simultaneously. It is part of the human condition to look for inspiration in the past. I think we can learn as much from moments when our courage fails.

New Acquisitions for Old Newbury (Originally published September 27, 2024)

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

"Hey, let's go to the Annual Meeting!" is not a phrase that is generally met with great delight, in my experience. It generally lands somewhere between listening to a long sermon and watching paint dry, in my experience.

Between financial reports and procedural votes, for the average member of a small museum, these meetings can feel like an obligation rather than a pleasure. And yet, we must have them.

If you were to ask any one of the staff members or volunteers at the Museum of Old Newbury what they most enjoyed over the past year, however, they would tell you about a special object, a meaningful experience, a new connection, and it is this passion that guided our September 11, 2024 Annual Meeting. Well, new acquisitions and great food.

So now, sit back and enjoy a short recap of the program, with special thanks to the guest presenters and to Bob Watts for these images. Not pictured - Sierra's presentation of the "masterpiece" cane, which you can read about here.

Operations Manager Shelley Swofford laid out a feast for our members, much of it donated by our board members, as James Dorau from Ipswich Ale Brewery and board member Eric Svahn tended bar.

Noah and Sam Clewely, our Future Leaders Interns, spent the summer cataloguing our military collection, focusing on artifacts from the American Revolution. Of particular interest is Long Tom, a gun whose extraordinary size - over 9 feet long - made it an interesting flagpole in this article from April 24, 1861. While this is not a new acquisition, their research brought its long and fascinating history to light.

Collections assistant Sierra Gitlin presented images from the Scott Nason Glass Plate Negative Collection, a very large group of images from Plum Island and Newburyport, donated in 2024. Sierra brought out other examples of glass plate negatives so attendees could get a sense of their size (see image of unknown man at the beginning of this article).

Family member Keith Lunt donated this daguerreotype of Samuel Henry Lunt and his daughter Sarah, along with a miniature painting on ivory and other records of his life. Shortly after this image was taken, Lunt died of "brain fever" or meningitis, in Mobile, Alabama, on July 28, 1865, while serving in the Union Army.

Archivist Sharon Spieldenner shared two important new purchases; a letter from Joseph Lunt aboard the prison ship Chatham in 1814, and a rare glimpse of Lord Timothy Dexter from a man who was passing through town in 1802.

This wedding dress, veil, and memory book, complete with receipts, photographs, and notes compiled by the bride's father, was a very recent gift to the museum, and costume historian Lois Valeo and yours truly shared it with the membership.

Harriett Currier married Leon Noyes on October 10, 1953 and the collection was given to the museum by her daughter. She recalled that her mother was "a kind, caring person and a great friend to many. She sang in the church choir at Belleville and was very close to her parents being the youngest at their Chapel Street home." Harriett (Currier) Noyes died in 2002, and is buried in Oak Hill Cemetery.

Board and collections committee member Monica Reuss, an American Art specialist, introduced three new paintings of the Newbury salt marsh. Lilian Wescott Hale (1880-1963) painted the larger work in the early 20th century. It is one of only two marsh paintings by women in the collection. The two smaller pieces are by Henry Curtis Ahl (1905-1996), who lived in Byfield and is best known for his coastal scenes.

Finishing out the presentations, the audience was introduced to one of the largest - and strangest - gifts received this year by the museum. This large section of an oak stump was used to hammer out punch bowls in various sizes by the Moulton family of silversmiths. It resided in the Towle offices for many years, and was left behind when the company was sold in 1994. As one of the oldest examples of silver working devices in the United States, it holds a place of honor in the carriage barn.

Bob Watts, board member and friend, caught us hamming it up behind the bar! Thanks to all of you who came out to celebrate another year of change and growth at the Museum of Old Newbury, and thanks especially to our presenters, board members, and volunteers. We love sharing some of our many new acquisitions with you!

The Magnetic Mr. Poyen, Part III (Originally published September 15, 2024)

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

Well, friends, we have returned for the third and final edition of the mesmerizing (see what I did there?) tale of Charles Poyen, member of the French refugee family of Poyens who escaped to Newburyport during the French Revolution. In case you missed the previous installations of this series, Part One is here, and Part Two is here.

When we last saw our gentleman friend, it was 1836, and Charles Poyen was just embarking on a career as a passionate advocate of Animal Magnetism, the belief that magnetic forces could be channeled and manipulated by trained mesmerists, and this process could cure disease, depression, and anxiety. It could even get you to work on time.

In February 1836, Poyen had gained a measure of success when the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (BMSJ) published an essay that included parts of his lectures on mesmerism. With interest thus piqued, Poyen managed to publish his translation of a French treatise on the subject. His real bread and butter, however, came from the lecture circuit.

There are no images of Charles Poyen on stage or otherwise, so we must rely on the description of the man given in the BMSJ.

"In person, Dr. Poyen was of a middle height; rather slender, yet well formed. Nearly one half of his face was covered, or rather discolored, by a naevus, of a dark-red hue, which greatly modified the natural expression. The cranial region for firmness was raised quite high enough to indicate obstinacy. He was habitually grave, thoughtful, industrious and studious, but not a close reasoner, nor by any means an original or profound thinker. Whatever was marvellous or extraordinary engaged his earnest consideration, particularly if it could be dragged into the service of the dearest of all interests—animal magnetism."

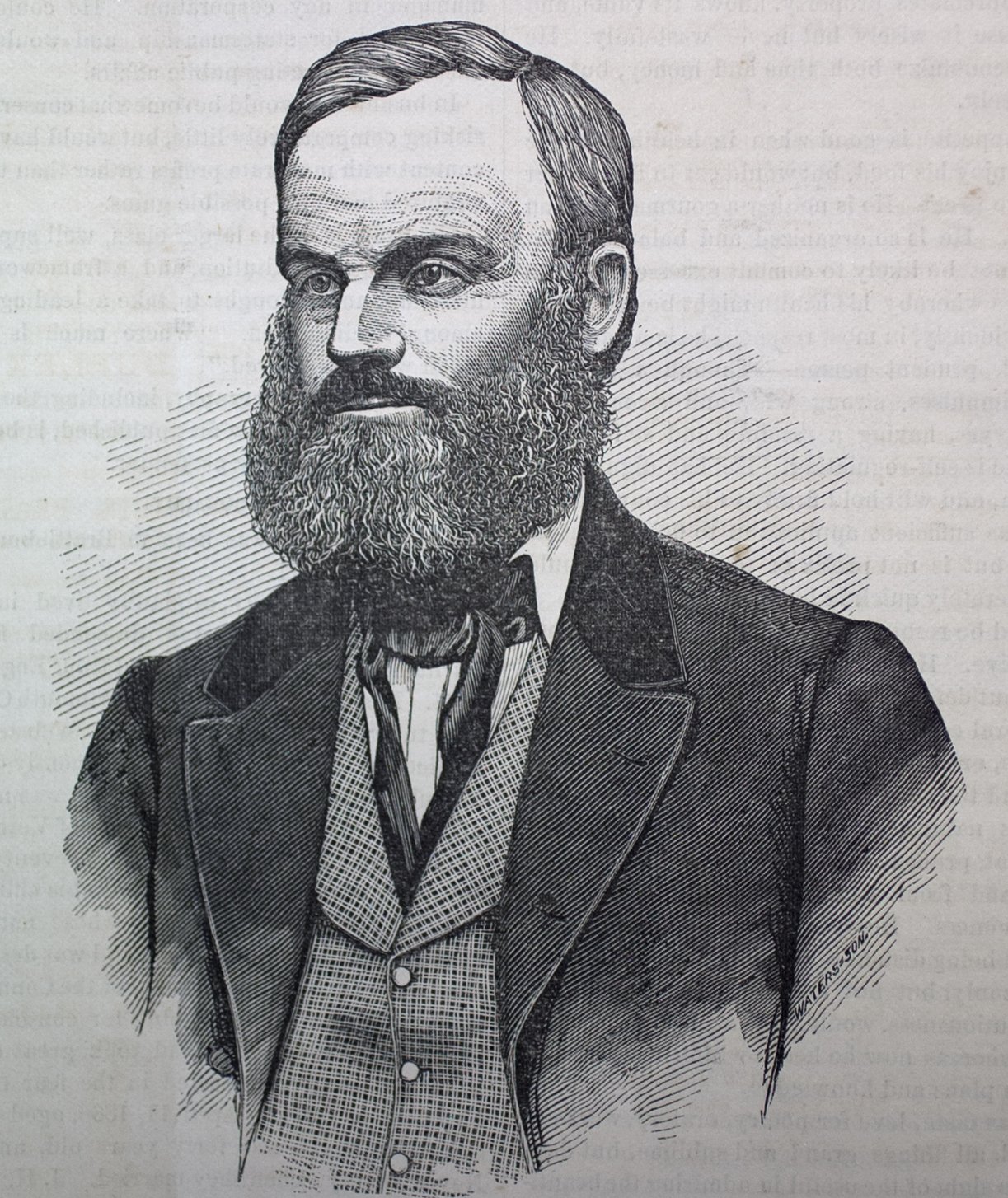

Phineas Parkhurst Quimby (1802-1866), famed spiritual healer, who was an early supporter of Charles Poyen.

Poyen went to Portland, Maine to see his cousin Abigail (Poyen) Whitter, who had married John Greenleaf Whitter's brother Matthew. While he was there, he gave some lectures which proved modestly popular. He also gained a few ardent fans, one of whom, Phineas P. Quimby, went on to famously mesmerize Christian Science founder Mary Baker Eddy.

As 1836 wore on, however, the lecture circuit was proving to be a bit of a slog. Worse yet, Poyen's book was hardly flying off the shelves. He needed money, and sent home to his family's sugar plantation in Guadeloupe for an infusion of cash. As author Emily Ogden noted, "had it not been for the proceeds of slavery, American mesmerism might never have gotten off the ground."

Thus financially fortified, Poyen headed off to the mill city of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, where his lectures could command a whopping 75 cents a head. This was several days wages for a (generally female) textile factory worker, so attended primarily by the (male) management of the mills. Women were a cheaper workforce than men, and the use of power looms meant that the labor, though dangerous and tedious, was not hard labor. Women were also considered more tractable and easier to manage. Still, productivity at the mills declined when their workers, who put in six 12 to 14-hour days a week, suffered from exhaustion, depression, and physical illness.

Poyen understood his audience, and his lectures began to focus on the benefits of animal magnetism for worker productivity. He also realized that his enthusiastic speeches needed a little more sparkle. He needed a dramatic demonstration, and for this he needed a partner.

Meanwhile, power loom operator Cynthia Ann Gleason was having stomach pains and trouble sleeping. She slept too much, too little or too late, and when she woke up, she felt groggy and listless. Though we may ascribe this to her grueling schedule, Niles Manchester, the part-owner of the factory in which she worked and also a factory physician, thought that Gleason might be "cured" through magnetism.

The Wilkinson Mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, built in 1810, would have been a familiar sight to factory worker Cynthia Ann Gleason. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Poyen and Gleason must have sensed an opportunity in their pairing. Poyen met with her, under the watchful eye of factory management, for over a week before their meetings culminated with Poyen placing Gleason into a trance. He “mentally requested the somnambulist (sleepwalker) to go to bed… and told her mentally to sleep until 8 o’clock exactly." And in the presence of senior management, Cynthia Gleeson managed to get her first full night sleep in years, awakening refreshed and ready for her 14-hour shift at 8 a.m. sharp.

Poyen remained in Rhode Island for nearly two months, and when he left to continue his lecture tour, he took Cynthia Gleason with him. They perfected their stage show, with Poyen putting Gleason into a trance and then demonstrating his power over her by having her identify objects held up behind her head, remain asleep despite loud noises or bright lights, and, in one notable case, pass out suddenly at a party while he magnetized her from another room in the house. Bells were rung next to her head, ammonia passed under her nose, pistols shot near her, but Gleason remained entranced. The pair became an overnight sensation and spent 1837 touring around New England. Poyen also published the scintillating Progress of Animal Magnetism in New England: Being a Collection of Experiments, Reports and Certificates, from the Most Respectable Sources. Preceded by a Dissertation on the Proofs of Animal Magnetism. In this book he responded to the criticism that if he really had such magnetic powers, they would work on anyone, not just the talented Miss Gleason. He was not at the height of his powers, Poyen explained, what with the tour and all, and because Gleason was an "experienced somnambulist", she required less of his "magnetic fluid" to get in the zone.

The Newburyport Herald took notice of the pair early in 1838, and was unimpressed. Under the headline "How to Wake a Somnambulist", the paper related a story from a demonstration in Waltham where someone had shouted "Fire", and Miss Gleason, "having no notion of being burned to a crisp", jumped out of her seat and ran.

In December, the Newburyport paper feigned sympathy as it reported that Gleason was "dreadfully frightened" when some young men shot a pistol near her head as she "pretended to be in a profound magnetic sleep". To make matters worse, in the ensuing melee, Gleason was kidnapped by a member of the audience, who "succeeded in running away with the fair imposter" and hiding her for two days.

The story of Gleason's disappearance spread across the country - it was reported from New Orleans to Bangor, Maine. In the end, despite his fervent, and perhaps genuine belief in the healing power of magnetism, it was all too much for the delicate sensibilities of our friend Charles Poyen. In the summer of 1839, he packed up and returned to France.

And then a curious thing happened. Other practitioners of animal magnetism took up the mantle and Charles Poyen's book sales picked up. As his fame grew and he contemplated a return to America, Charles Poyen died suddenly in Bordeaux in 1843, just 36 years old.

Charles Poyen's cousin by marriage, writer and journalist Matthew Franklin Whittier (1812-1883). Private collection.

Animal magnetism obsessed the nation in the 1840's and beyond, attracting the attention (and derision) of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Nathaniel Hawthorne, and even making its way into Moby Dick in 1851 as Captain Ahab wields hypnotic power through his "magnetic life". It even became a trope in pornographic literature of the time, with writers describing debauches with mesmerized women.

By the 1860's, animal magnetism had been eclipsed almost entirely by spiritualism, which offered a grieving nation the ability to communicate with the dead. Still, here in 2024, amazon.com will happily sell me a magnetic fork with which to heal myself and my loved ones, and the National Institutes of Health includes magnetic therapy on its list of alternative healthcare options.

Much as I will miss our adventures, I will pull the curtain on Charles Poyen, for the moment anyway, with the kind words spoken of him by his cousin-in-law, Matthew Whittier, in the Portland (Maine) Transcript.

Doctor Poyen...will be remembered as the first propagator of the now popular science of Animal Magnetism in the United States. (He) seemed to see with prophetic vision through the clouds of prejudice the almost universal favor with which that theory is now received. Doctor P. was...an urbane, upright gentleman."

The Magnetic Mr. Poyen, Part II (Originally published August 30, 2024)

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

We're back with another scintillating edition of How to Magnetize Friends and Influence People! In case you missed our last episode, which offered a peek into my bouncing brain, once described as "squirrels locked in a small room", it is linked here.

We met Charles Poyen, a member of the Poyen family who landed in Newburyport along with other refugees from the French West Indies, learned a little bit about Animal Magnetism, and discovered that healing with magnets is still very much a thing.

This episode begins a generation before, in the 1790's back in Guadeloupe, with a murder or two. We are told by the nonagenarian Sarah Smith that the French Revolution "reached the French West Indian colonies with even more intense cruelties than in the mother country." This beggars belief somewhat, as the mother country was cruel as can be, but let's just say there was plenty of violence to go around. The rather more cool-headed John J. Currier said simply that there were "scenes of anarchy and confusion" in the French West Indies.

Sarah Smith was closer to the mark. The French Revolution came to Guadeloupe like a wrecking ball. The wealthy planters were tied by blood and money to the aristocracy of France, and the revolutionaries hated them equally. To further stoke the flames, the revolutionaries abolished slavery, upon which the West Indian economy was based, and the planters invited the hated British to invade in order to preserve the institution of slavery in 1794.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. Two years earlier, the Poyen family, wealthy sugarcane planters from the village of Habitation Piton near Saint-Rose, Guadeloupe, were attacked. The oldest and youngest sons, Robert de Poyen and Saint Sauveur de Poyen were "killed by the brutal mob of republicans", according to Smith. 51-year-old Pierre Robert de Saint Sauveur Poyen fled with his three surviving sons, two daughters, and a step-nephew, Count Francis de Vipart (François Félix Hector de Vipart Morainvilliers). They managed to get aboard a Newburyport brig, one of many sent to bring molasses and sugar back to the distilleries that dotted the waterfront. The family arrived in Newburyport in March 1792.

I'll get back to Charles Poyen, I promise, but first, I must tell you about the Poyen step-nephew, Count Francis de Vipart. Well, more to the point, I must tell you about Mary Balch Ingalls, distant relative of Pa and Ma and Laura Ingalls, and my 4th cousin. Apparently after some time in Newburyport, the Count made his way up river, and in 1805 he wooed and married Mary Balch Ingalls, just 18 (he was 27 or 28). She died three years later and was buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Haverhill. The bereaved Count returned to France and eventually to Guadeloupe.

The poet John Greenleaf Whittier, whose brother married the Count's cousin, Abigail Poyen, wrote a romantic poem about the grave of the young Countess. The poem inspired such paroxysms of grief that her grave became a pilgrimage site of sorts, and then people started chipping off bits of it as souvenirs. The family erected a cage around the stone to protect it, which did the trick for many years, but the stone is now gone - some say hidden away for safekeeping.

The rest of the Poyen crew settled in Newburyport, at least for a few years after their arrival in 1792. Pierre, called "Peter" in his probate record, and entirely without a first name in the Newburyport death record, didn't last the year, dying of "loss of home, change of climate, grief and anxiety", according to Smith.

Pierre's son Joseph stuck around as other family members found their way back to Guadeloupe. And what does a young French aristocrat do for cash in late 18th century Newburyport? Open up a dancing school, naturally. Four years later Joseph, now styling himself as "Poyen Rochmond", placed this ad in the Newburyport Impartial Herald.

Two years after that, in 1798, he was also teaching "the useful and necessary art of self-defense" by broad sword. He also apparently played the violin, which he put to good use as a fiddler for country dances later in his life.

Joseph Poyen married a local gal, Sally Elliot, in 1805, and their nine children and their descendants spread across Haverhill, Amesbury, and Merrimac, where they can still be found today.

The Poyen Sampler, wrought c. 1819, likely by Elizabeth Josephine Poyen, is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

So many people to meet! But, I have promised you a story about Charles Poyen, nephew of Joseph the dancing, fiddling self-defense instructor. Charles Poyen was the son of Mathieu Augustine Poyen, Joseph's younger brother.

Many of the French refugees returned to Guadeloupe once it was safe to do so, and, of course, once Napoleon had reinstated slavery in 1802, making the sugar plantations economically attractive once again. Charles Poyen was born in Guadeloupe around 1806, where his father had returned to re-claim the family plantation.

When Mathieu Augustine Poyen died in 1827, he left a large, profitable plantation, enslaving some 90 people. Charles inherited this wealth along with his mother and siblings, and seems to have set off to France to study medicine. Sometime in 1832, he developed a painful and complicated "nervous disease" that effected his stomach and right side. He was treated by a doctor who employed a clairvoyant named Madame Villetard. Poyen was healed, he began reading voraciously about animal magnetism, and he returned to Guadeloupe to try it out on the people his family and others enslaved. Thus convinced that "the human soul was gifted with the same primitive and essential faculties", in other words, anyone could be mesmerized.

Determined to spread the word of healing through animal magnetism to America, Charles Poyen sailed for New England and descended upon his uncle Joseph Poyen, who was then living in Rocks Village, in 1834. He stayed for five months before moving on to Lowell, where he set up shop as a French and art teacher.

Charles Poyen appeared in the Lowell directory in 1836. It is not known, though it is likely, that the Louis Poyen staying at the same place is a relative.

Charles Poyen claimed that he never mentioned animal magnetism for six months when he was first living in Lowell, until he found himself in conversation with the mayor, Elisha Bartlett who seems to have convinced him that there was a market for his passionate advocacy of mesmerism. Poyen, thus encouraged, set out to find a publisher for an existing treatise on the subject.

When no publisher bit, Poyen decided a round of lectures and demonstrations of the mesmeric trance that was the cornerstone of the practice of magnetism would help him build an audience. January 1836 found him lecturing in Boston. In February, the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal published an essay, then his translation of the Report on the magnetical experiments made by the Commission of the Royal Academy of Medicine, of Paris was published in June.

Though his star was certainly on the rise, in the fall of 1836, he sent home to Guadeloupe for money to continue his lecturing, as it was not yet profitable. It was not until he took his lecture tour to the mill town of Pawtucket and met Miss Cynthia Ann Gleason that he became a real celebrity.

Well, friends, here we go again. I'm out of space with so much more to tell. Stay tuned for the next newsletter, in which I promise to wrap it up already as Charles Poyen uses magnetism to get the factory gals to work on time, launches the career of Miss Cynthia Gleason, and inspires generations of magnetizers here in Newburyport.

The Magnetic Mr. Poyen (Originally published August 16, 2024)

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

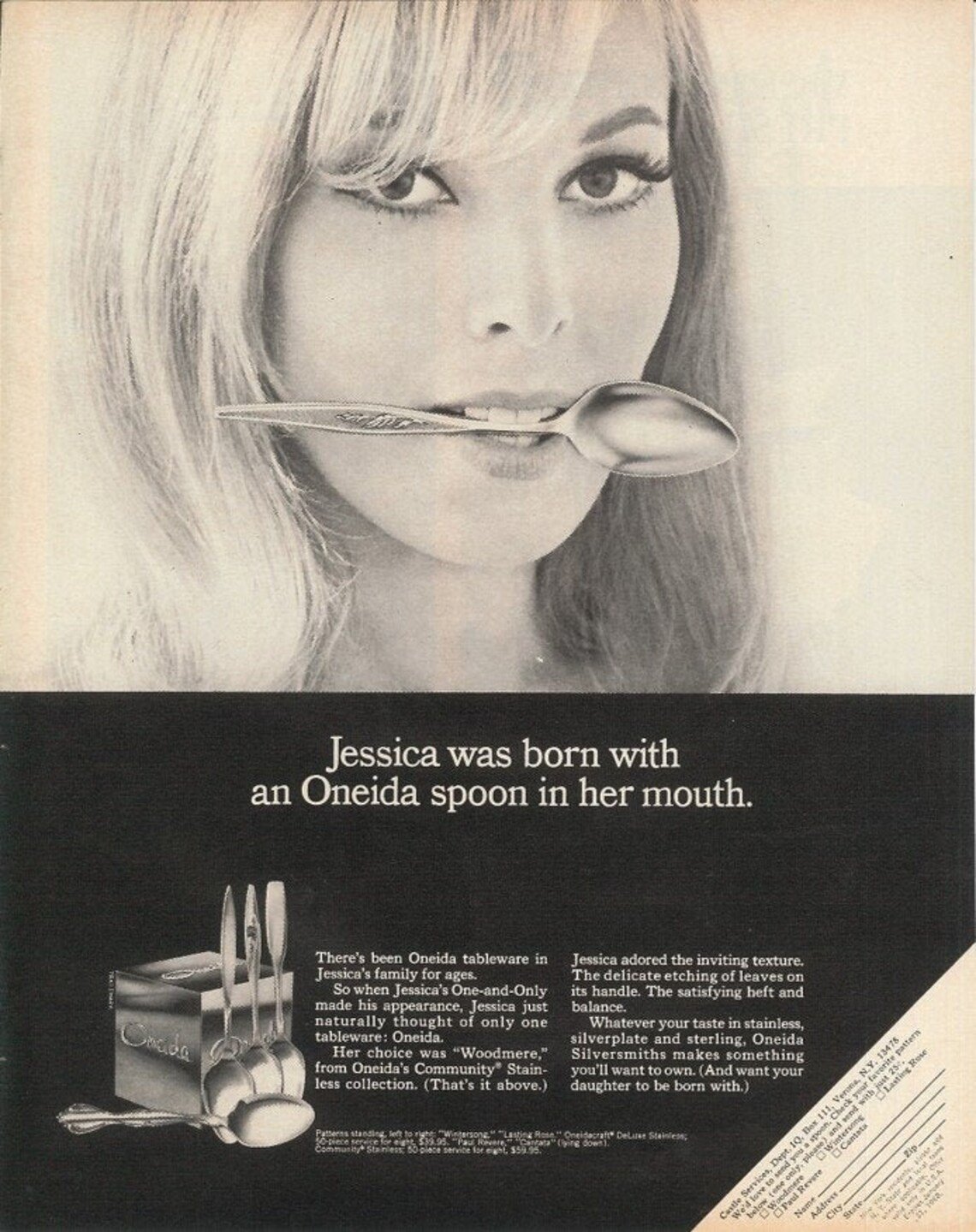

Late 18th century print depicting the healing power of Animal Magnetism. Sufferers hold painful or diseased body parts against iron bars connected to the bacquet, a wooden tank filled with magnetized water. The woman on the left is in a mesmeric trance, having been magnetized by a healer. Image courtesy of Wellcome Images.

Well, my friends, Amazon Prime Day seems to have turned into numerous Amazon Prime Days, and I somehow found myself wandering down that technicolor rabbit-hole a couple of weeks ago. When I came to my senses some minutes (hours?) later, I was staring at an image of a hand pressing a knobby fork into the back of a presumably consenting adult. It promised HOLISTIC HEALTH BENEFITS! I was invited to “Harmonize Body Pathways” and “Release Trapped Emotions”, among other things. The fork thingy, you see, was magnetized, and so assaulting yourself or a friend with it, in a circular motion, could accomplish amazing things.

This all rings a bell, thought I. I had been in the middle of a bit of research on the crazy story of the escapees/refugees from the islands of Dominica and Guadeloupe who came to Newburyport during the tumultuous years of the French Revolution. It is a wild tale, and one which has been asking for attention recently.

To make a very long, very interesting story a bit shorter, Newburyport and the French West Indies, especially Guadeloupe, had a long and prosperous relationship based on, well, slavery. By which I mean that the sugar, molasses, and rum that were flowing into Newburyport in the late 18th and early 19th century, were produced on French plantations that depended on enslaved labor. Nearly 80% of the population was enslaved. With the French Revolution in 1789 came waves of violence against the royalist plantation owners in Guadeloupe, who fled for their lives, some with the help of their Newburyport friends and business partners. There are stories of planters escaping after members of their families were killed, frantically rowing out to Newburyport ships in the harbor. We know of at least two captains, William Bradbury and Offin Boardman, who brought refugees to Newburyport from the French West Indies.

This headstone in Old Hill Burying Ground memorializes Pierre Poyen, one of the French refugees who came to Newburyport during the French Revolution, dying a few months after his arrival. It reads:

SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF

MR. POYEN DE ST SAUVEUR

WHO FOR A LONG TIME WAS

AN INHABITANT & A REPUTABLE

PLANTER ON THE ISLAND

OF GUADULOUPE

DIED OCTOBER 14TH, 1792

AGED 52 YEARS

In my years of researching and writing, I have learned to listen to the people and events that rise up and knock on my metaphorical window – there are stories that want to be told. Often these appear as a series of seemingly unconnected events. I notice a gravestone while looking for another person, or a last name suddenly seems to be coming up all over the place. I’ll visit another museum and there they will be, on an object I had no idea existed or in a book I’ve never read. Or I will wonder why I paused on an Amazon listing for a magnetized fork.

Here's where I take you inside the squirrely warren of my brain. Follow me. I have been researching a sampler made by a Mademoiselle Marie Dumans from our collection, one that we know very little about. With the help of several other researchers, including the intrepid Ellie Bailey, we have determined that the sampler is likely connected to the family of a Charles Joseph Benjamin Cherot Dumaine, who was baptized on April 17, 1801, in Newburyport.

Then, on a trip to Old York, I came to a dead stop in front of a painting of Nathaniel Barrell, who was familiar to me from my days working at the Sayward Wheeler House, owned by my former employer, Historic New England. It was not the subject, but the artist that grabbed my attention.

Newburyport’s Moses Dupre Cole, whose work is also well represented at the Museum of Old Newbury, was born Moise Jacques Dupree Cools de Godefroy, in Bordeaux, France. He fled from St. Lucia with his father in 1795 and landed in Newburyport. Then, at Old Hill Burying Ground, I stumbled on the grave of Jaque and Louis Mestre, who died in 1793 and 1792, age 21 and 17, respectively. And, you may find this a stretch, but Annabelle, who has been working with me since she was 17 years old, and who co-wrote the main story in this newsletter, is headed to France for graduate school next month. And then there’s the Olympics. Suddenly France, and the French West Indies in particular, seems to be everywhere.

Portrait of Nathaniel Barrell (1732-1831) by Moses Dupre Cole (Moise Jacques Dupree Cools de Godefroy). Courtesy Historic New England.

And what, you may ask, has this to do with the magical magnetic fork? Back into my squirrely brain we go. For many years I have been interested in the social and cultural impact of early photography, particularly of the sort that claimed to capture images of spirits and other supernatural phenomena.

There are adherents of spirit photography today – just visit Salem to have your aura snapped – but they were big business in the 19th century, when many people’s understanding of the photographic process was rudimentary enough to render them gob smacked at what we would see clearly as a double exposure.

One such practitioner, Edouard Isidore Buguet, who I had studied at length in graduate school, began taking supernatural photographs in 1874, and was a fervent believer in animal magnetism, also known as mesmerism, the belief that the body exerted a magnetic force that could flow between bodies if connectivity was established, generally through some sort of fluid. If this magnetic force was blocked, it could cause a host of problems from depression to infertility and beyond. Sufferers would be “mesmerized” to remove these blocks and promote all the benefits that the amazon.com fork promised me. Buguet routinely had himself and his cameras and equipment mesmerized to remove obstacles to, well, double-exposing plates and then selling them to gullible French people for an exorbitant amount.

Now, if you haven’t thrown your computer across the room in frustration while screaming, “GET TO THE POINT,” you’re a better person than I am. I had to stare blankly into the middle distance for a long time to figure out what all these things had to do with each other.

And then it came to me (as in a mesmeric trance). One of the families that had escaped from Guadeloupe was the Poyen family. Their story, like so many others, is a bloody one, with twists and turns that will make your head spin. More on that later. And it was Charles Poyen who brought mesmerism to the United States from France, making it so popular that the word “mesmerized” and the term “animal magnetism” have became part of our common vocabulary. I also “met” Charles Poyen in graduate school. I was briefly obsessed with how animal magnetism became the great obsession of American literature in the 19th century, captivating Edgar Allen Poe, Herman Melville, and Nathaniel Hawthorne, among others.

The Poyen family coat of arms, as rendered by Sarah Smith Emery in her 1879 book Reminiscences of a Nonagenarian.

How many Poyens are there in France, I asked myself. Must be thousands. I did a quick bit of research on Charles Poyen. Born in Guadeloupe in 1808…that seemed promising, but the Poyen family that escaped to Newburyport had arrived in 1792. Probably not. And then, the smoking gun…

From an April 1960 article in the Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences (I cast a wide net) “Poyen sailed in 1833 for a sugar plantation owned by his relatives in the French West Indies…His health had shown little improvement, however, and so he decided to visit the United States to see if another change of climate would benefit him. In late 1834 he landed at Portland, Maine, and proceeded to Haverhill, Massachusetts, where lived a paternal uncle who had immigrated to the United States at the time of the French Revolution.” Haverhill? Had to be the same family. And they are – Mesmerizer Charles Poyen’s father, Mathieu Augustine Poyen, came to Newburyport with his brother in 1792, then went back to Guadeloupe to reclaim their sugar plantations after Napoleon reinstated slavery in 1802.

Portrait miniature of Abigail Rochemont Poyen (1816-1841), Charles Poyen's first cousin (once removed), who married my cousin (but didn't everyone?).

As I have repeatedly claimed, if you spent more than ten days in Newbury(port) during your baby-making years, I am most likely related to you somehow, and this has proven to be true even of Charles Poyen. His first cousin (once removed) Abigail Poyen, married Matthew Whittier, brother of the poet John Greenleaf Whitter, both my second cousins six times removed. So we zip Charles Poyen into my family tree and we are off.

And now, as with the subject of my last blog series, my dearly beloved John Bartholomew Gough, I have exceeded the word count for this newsletter. Stay tuned as we meet the rest of the Poyen clan, Charles Poyen becomes a clairvoyant management consultant for Lowell factory workers and his distant cousin (by marriage) Elisha Perkins begins the healing silverware tradition.

Other Duties as Required... (Originally published August 2, 2024)

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

Images and video in this story are courtesy of Bob Watts, Shelley Swofford, Steve Crosby, and Alex Yablin. This one is from Bob.

When I began working at Historic New England nearly 25 years ago, I was presented with a job description that closed the "Primary Responsibilities" section with "other duties as required". It made me chuckle then as now, since this one line seems to sum up what museum work can involve - literally anything.

Over the course of my career, I have invoked this line when I found myself called to crawl in a manhole with a video camera on my head, fish a live muskrat out of a rain barrel, sleep on the ground with an ailing sheep, test a stuffed pheasant for arsenic, drive a fire truck...the list goes on and on. I can honestly say that no two days are alike. I would go so far as to say that on any given day I must have at least two outfits at the ready - one for looking like I am the director of a venerable museum, and one for crawling around in an attic. Yesterday I had a three-outfit day, and the third outfit involved flying down Federal Street with a model ship on my head.

Other duties as required.

It began with James Brugger, an esteemed board member and friend. He suggested that we should enter a Museum of Old Newbury bed in the Yankee Homecoming Bed Race, organized by the Lions Club. Because another part of museum work involves being chronically short of staff and funding, I gave my wholehearted consent, if it did not cost the museum any money and the work was done by volunteers.

Enter Steve Crosby, preservation carpenter extraordinaire, remembered by many as the man who staged the terrific Halloween tableaux on Marlboro Street for years. James and Steve and I got talking at a party, and we were off to the races, pun intended.

It began with an idea and a drawing...

The concept was fleshed out by Steve and James. Supplies were ordered, measurements and weights debated, race rules pondered, and slowly but surely, thanks to Steve's incredible plywood-bending skills, the bed took shape.

Now, just in case you are scratching your head at the whole idea of a "bed race", let's back up for a moment.

On June 27, 1984, the Newburyport Daily News announced the first running of the beds as part of Yankee Homecoming. The rules were very similar to those of today. The bed must be of a standard size, there could be a maximum of 5 runners, and someone must be in the bed.

In 1984, the bed races started at the corner of State and High Streets, raced down High Street, then down Federal Street, and terminated at Atwood Street. It was twice the current 1/4 mile length. Nobody was sure how it would go, including American Legion commander Alan "Buster" Driscoll. "I didn't think too much would come of it." Driscoll said. It was wildly popular in the end, with over 30 beds registered.

Bed races were not new in 1984, though the "ladies bed races" held in Newbury since the 1950's were very different. In these races, women were tucked into bed, and when an alarm sounded, they had to don full firemen's outfits, run across a field, and spray targets (and sometimes each other) with fire hoses. This was generally held as part of a benefit for a local fire department, as was the case here in this 4th of July event in Newbury in 1969.

We are not alone in our fondness for combining beds and racing. Rutgers University has been holding bed races since 1966, the same year that the Knaresborough Round Table in North Yorkshire, England, began holding bed races that covered a grueling 2.4 mile course. Since 1990, Kentucky Derby Bed Races have been held in an indoor track.

With the decline in American Legion membership in the area, the Newburyport Bed Race ended in 1995, but was revived in 2002 by the Lions Club. It has been a steady crowd favorite at Yankee Homecoming celebrations ever since.

Meanwhile, in the carriage barn of the Cushing House, Steve and James were working tirelessly on the Museum of Old Newbury racing bed. As the process neared completion, other volunteers jumped in. Shelley painted and added the clock faces with Sharon's help. I donated an old porch chair which was cut down, stabilized, and painted. My husband, James, recorded chiming clocks and lent his portable speaker and his tricorn hats. We had fans made out of the memorable face of our beloved Landlocked Lady, a figurehead who never went to sea.

And then there was the small matter of the runners. James secured the services of the Charles River Rats Run Club to speed us to victory. And then, one day before the big race, the bed was declared ready, and a hearty crew of interns, volunteers, and staff took her for a test run. Our archivist brought in a hat with a model ship screwed atop. My entire outfit changed to accommodate that stellar chapeau.

Race day dawned hot and humid. The interns and staff donned tricorn hats and grabbed fans to hand out. The runners assembled, and Steve and James dressed to the nines, though Sharon outdid us all. I hopped aboard and we walked down to our place at the head of Federal Street.

After a fun wait while we fraternized and sampled the beverages brought by the runners of several nearby beds, it was our turn.

We were fifth in line to race, and though the lads put in a tremendous effort, in the end, the wheels on the bed went wonky and we had to slow considerably. Still, the sirens blared and the crowds cheered and Old South rang her bells, and we hurtled down the street and it all went by in a flash.

After the race, the runners wheeled the bed back to the museum, trailed by the laughing interns and Shelley in their tricorn hats. James and Steve wandered off to their respective parties, and I walked slowly back up Federal Street in search of my family.

I will never forget all of us at the starting line singing La Marseillaise in honor of Annabelle's looming departure for graduate school in France, or how Shelley gave me her fan, Sharon her hat, my daughter Meg her dress. I will think of Steve in the carriage barn late at night and early in the morning, and James with his buckle sneakers, always thinking of new things to try.

I will remember each of you who came over for a hug and a high-five, the little boy who asked to touch my wings, the ringing of the steeple bells, laughing with Kristin as we waited for Senator Tarr, Bob behind the camera with his megawatt smile.

After the race, a photographer asked me to step into the street for a picture, and the smile on my face says it all. I am so proud of all of us. So much effort and thought went into this project, all in service of this wonderful museum.

Joy and friendship and love and wearing wings and a ship on my head are not in my job description, friends. Thank goodness for Other Duties as Required.

The Mysterious Disappearance of John B. Gough: A Temperance Blog, Part IV (Originally published July 19, 2024)

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

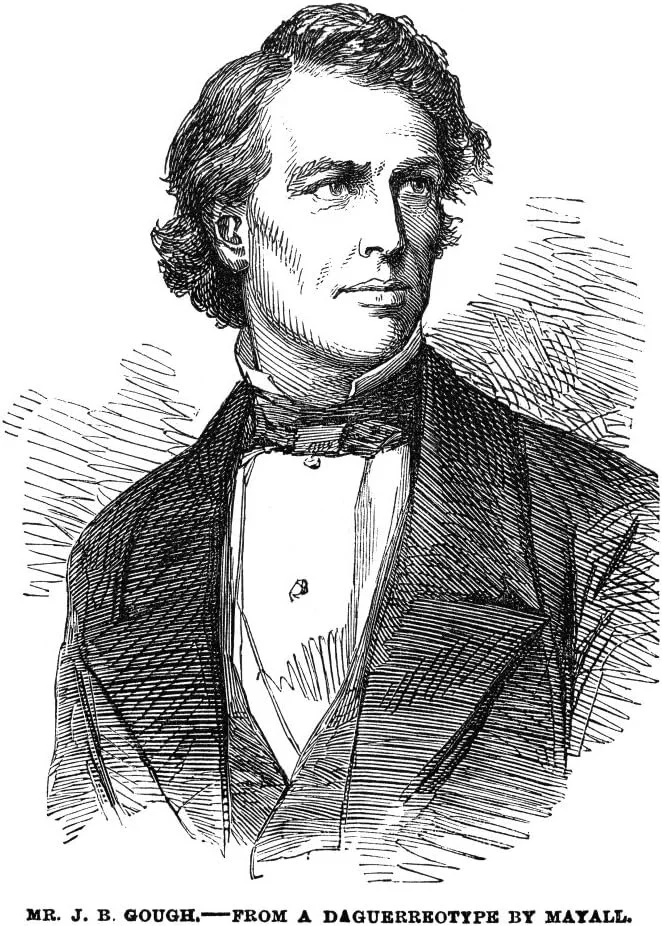

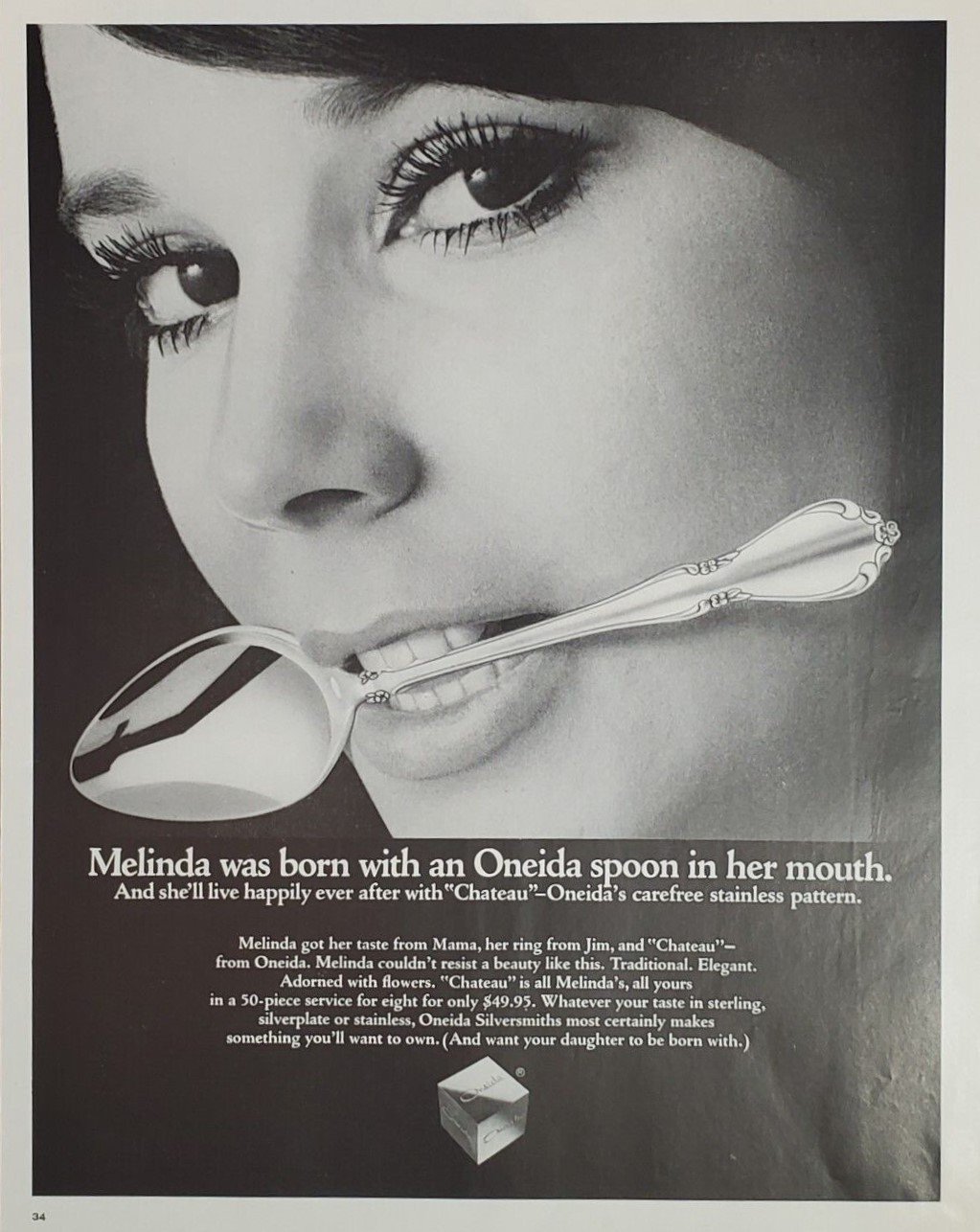

John Bartholomew Gough, from his 1880 memoir, Sunlight and Shadow or Gleanings from My Life Work, Comprising Personal Experiences and Opinions.

If you missed it, read John B. Gough Part I here and Part II here and Part III here.

Well, dear reader, over the past months, I have spent a great deal of time with the fascinating personage of Mr. John Bartholomew Gough. I have wandered down the dark alleys of Newburyport, Boston, and beyond with him, read his speeches and his memoirs, galloped up and down his family tree, perused his newspaper ads and his court records. It seems impossible that I had never heard of the man until Scott Nason dropped him into my lap a few months ago.

But, I wager none of you had heard of John B. Gough.

In his time, however, he was as famous as Charles Dickens. He was known as the Prince of the Lyceum. He amassed an international following and a fortune. When he died in 1886, the New York Times wrote that he "was probably better known in this country and in Great Britain than any other public speaker."

Just after his death, Gough was impersonated by the famous actress Helen Potter - from the waist up, at least. Potter avoided censure by hiding her skirted lower body behind a table until the end of the show. Her other famous subjects? Abraham Lincoln and Susan B. Anthony. I'll bet you've heard of them. But John B. Gough? Fame is fickle, friends.

But for now, let us pause our musings on the vicissitudes of fame, and return to a younger John B. Gough, a rising star on the temperance stage, who has just exited Newburyport. It is May, 1845, and Gough has just managed to extort fifty bucks from young Jacob I. Danforth, who served him a drink (or two, or three) at his family's Washington Street restaurant after Gough delivered a stirring public lecture on the evils of drink, and then blabbed about it.

THAT John B. Gough looked like this...

Above - This etching, from the 1845 Autobiography, was made just before he bellied up to the Danforth bar (or didn't, depending on who you believe) in Newburyport.

Below - newspaper advertisement for Gough's first Autobiography, May 12, 1845.

Despite the kerfuffle in Newburyport, 1845 was a banner year for John B. Gough . He had just published the first of several autobiographies, this one with the catchy title An Autobiography by John B. Gough, and book sales were brisk, with ads placed in newspapers from Vermont to Georgia. After his return to Newburyport in May, Gough continued his frenetic pace on the temperance lecture circuit, with summer engagements from the top of Vermont to southern Connecticut. By mid-June, he had made 120 speeches, nearly one a night, quite a feat at a time when travel by rail was still in its infancy. A Gough Temperance Society sprang up in Baltimore, Maryland. He headlined the Rhode Island Temperance Convention. Everything was coming up roses.

Newspapers across the country carried the votes of temperance associations to secure funds for a Gough appearance. On June 10, 1845, the Milledgeville, Georgia Southern Recorder was already planning a Georgia trip for Gough in the fall of 1846.

And then, on September 6, John B. Gough vanished.

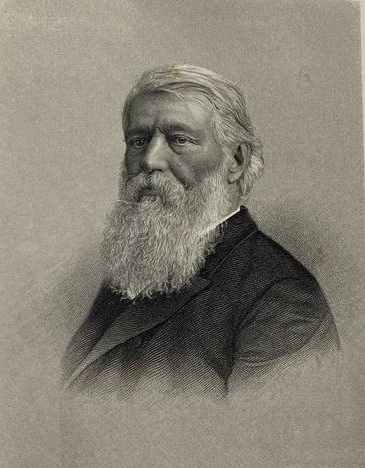

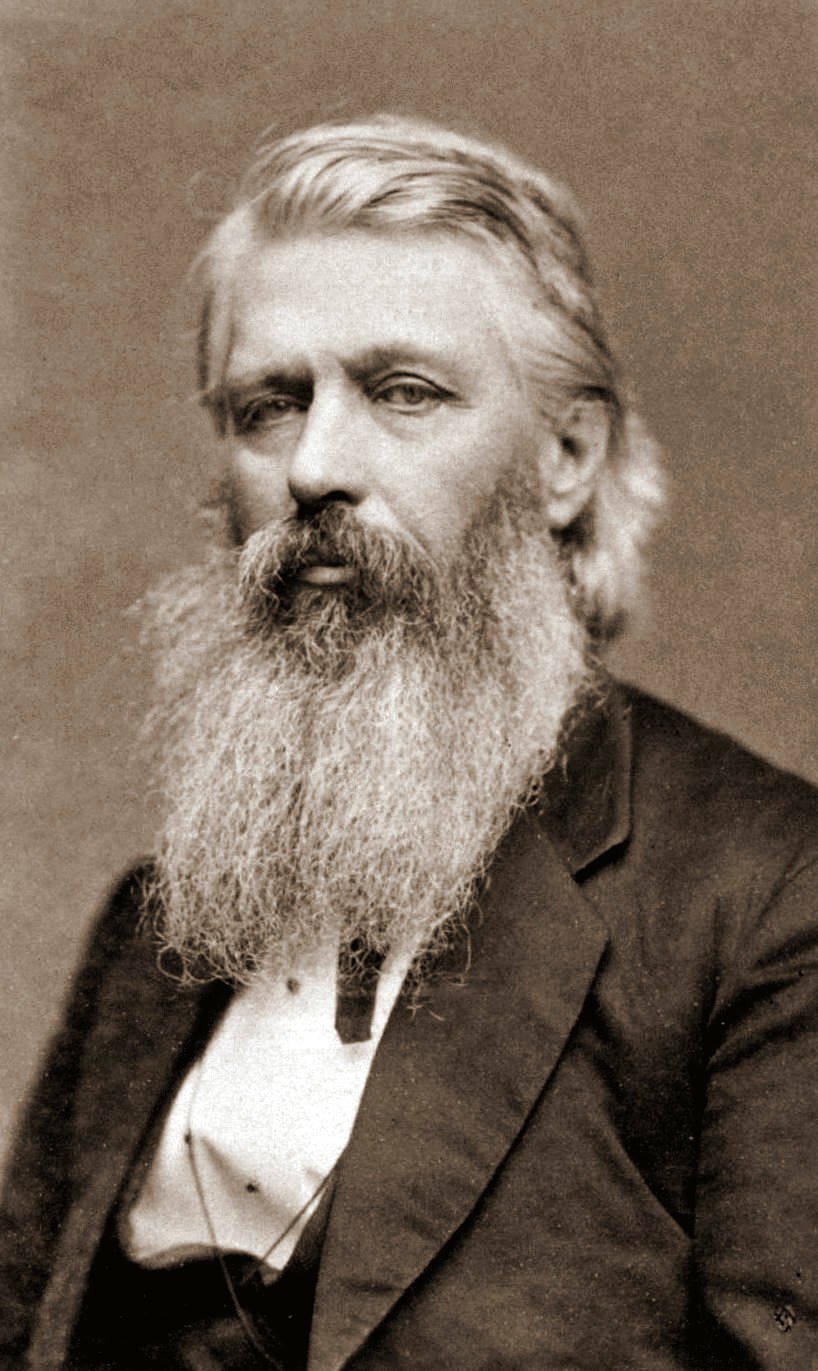

Above - John Bartholomew Gough, engraved by D.J. Pound from a photograph, from The Drawing-Room of Eminent Personages, Volume 2

Below - This notice from the New York Express was republished in the Newburyport Herald and offers a wonderful description of John B. Gough in 1845. He has "long, straight black hair, dark complexion, sharp features...," and was heavily accessorized in gold and carrying a small fortune in cash and gold.

Gough had been missing for a week when, on September 11, placards went up around Manhattan offering a reward for his return. The following day, all the New York newspapers carried the announcement. On September 13, with a certain amount of glee, the Newburyport Herald, which had ultimately come out in favor of Danforth in the May controversy, carried the news.

The Herald was not alone. Gough's disappearance was reported across the country, and almost immediately, opposing rumors began to circulate. Supporters of Gough suspected foul play driven by the "rum merchants" whose business was threatened by temperance. Critics began to hint that Gough had fallen off the wagon before, though few would say so outright for fear of a slander charge.

Above - The steamer New York brought John B. Gough from New Haven to Manhattan, arriving on September 6. Courtesy of the Mariners Museum.

Below - The Five Points neighborhood in New York where Gough was found was notorious for vice and squalor in the 1840's. Courtesy of the New York Library.

And this, dear reader, is where things get interesting. It seems that Gough had taken the steamer from New Haven, arriving in Manhattan on the morning of Saturday, September 6. It was supposed to be a quick trip back to the city of his youth. After a weekend of meetings in the city, Gough was scheduled to hop a train to Albany to meet his wife (he had remarried in 1843) and head to Montreal for a series of lectures.

Gough checked into room 63 of the Croton Temperance Hotel at 142 Broadway, dropped his bags, changed his clothes, had some tea, and went back out. He stopped in at the bookstore of Saxton & Miles, and then...nothing.

By the time news of Gough's disappearance reached Newburyport, he had been found, on September 12, by two reporters from the Police Gazette, in "a back building up an alley", in "the garret of a house of ill fame" on Walker Street. He was brought to the house of a friend in Brooklyn. This friend and temperance supporter, George Hurlbut, despite finding Gough in a "state of delirium", managed to cobble together a narrative, complete with quotes, to explain where Gough had been. It strains credulity now, and certainly did then as well, though Gough stuck to the broad outlines of the story for the rest of his life.

"On Friday evening, he left the Croton Hotel to take a walk, preparatory to retiring for the night, went into Saxton and Miles bookstore, and afterwards stopped to look at the prints in Coleman‘s shop window, where a young man accosted him as an old acquaintance. Mr. Gough did not at first recognize him, but afterwards remembered that he worked with him several years ago in the Methodist book concern. “This is a fine new business you are engaged in”, said the man. “It is new to me," replied Gough, "but much happier and more congenial to my feelings than my old acquaintances, and I hope that you too are on the side of temperance”. "No", said the young man, "I can’t do that. I take a glass once in a while when I want it."

Does this sound like the incoherent ramblings of a man who was at death's door after a week-long bender to you? Me either. It seems more likely that his team was in full damage control and significantly embellished (or invented) the reason for his disappearance.

To make a very long, very convoluted story shorter, the young man in question, whose name Gough later remembered as Jonathan Williams (he also said Williamson), finally prevailed upon Gough to have a soda water with him in a little place on Chatham Street. Gough had his water with raspberry syrup. Shortly after, Gough "very soon became giddy", bellied up to a Bowery bar, ordered a brandy, and that was pretty much all he remembered until a week later when Mr. Camp and Wilkes of the Police Gazette poked him with their canes.

Here's Wilkes. "There we found him - John B. Gough, the mere shadow of a man, pacing the floor with tottering and uncertain steps. He was pale as ashes; (his eyes glared with a preternatural luster), his limbs trembled, and his fitful and wandering stare evinced his mind was as much shattered as his body. The pompous horror had dissolved from its huge proportions, and shrunk into a very vulgar and revolting commonplace. The man was drunk. That was all that was the matter with him — the man was drunk (and apparently did not carry his liquor well)." Ouch.

The location of the Croton Hotel is marked in red on this 1845 map, with the house where Gough was found is in blue.

What is certainly true is that when Gough was found, he was full to the brim with liquor. He was also "relived of a considerable quantity of laudanum (opium tincture)". There was only one possible explanation, he said. The raspberry soda was drugged by haters of temperance.

The temperance community, by and large, rallied behind Gough's version of events. Others were not so kind. Gough's story had several glaring holes. First, no one could identify a Jonathan Williams (or Williamson) who worked with Gough. Second, there were no soda shops in Chatham Street. Third, he had been seen walking quite willingly along the pier in the company of a woman. Stranger still, he had not been robbed. Gough was found still in possession of his gold watch, his gold ring, and a quantity of cash, though at some point he had switched shirts with someone and lost his gold buttons.

Most damning of all, this was not the first time Gough had hauled down to New York for a bit on the side, according to Wilkes.

"One day, about six or seven weeks previous to the 6th of September, the period of Gough's last arrival in New York, he accosted a certain tall, good-looking woman dressed in black and with dark hair and eyes while in the Broadway stage. This was between the hours of nine and ten o'clock in the evening. In the conversation which ensued, he said he had been out riding on horseback, that he was very much fatigued, and that he wanted to accompany her home. To this she replied that she could not take him to her home, but would take him somewhere else. The arrangements being thus concluded, she conveyed him to the same house in Walker street which he afterward rendered so memorable."

Gough effectively went into hiding through the rest of September, as newspapers across the country continued to publish scintillating details of his misadventure. Gough's camp released news items that he was terribly ill, that he was unable to speak, that he would make a full confession when he was well. So great was the public demand for an update that several fake confessions made the rounds.

On Saturday, October 4, the Newburyport Daily Herald published Gough's full confession on the front page. It seemed that, as one newspaper put it, "the lost star of temperance went down ingloriously between Venus and Alcohol." the Police Gazette was less polite.

"Notwithstanding his solemn vows and pledges before the altar of his God, and his sacred pledges before man, (he) returns back to his vomit, and seeks solace for his forced abstemiousness in the secret orgies and caresses of drunken prostitutes."

In the end, however, John Bartholomew Gough must have known that Americans love a comeback. Now more famous than ever, forgiven by his church, his movement, and his wife, Gough rolled the drugged soda water/brothel story into his stirring temperance tale and took it back on the stage. Audiences laughed, they cried. Maybe they thought he was a loveable rogue. Whatever the attraction, over the next four decades, John B. Gough performed steadily on the temperance stage in the United States, Canada, and Europe. He would often say that he wished to die in the harness, and it was on the lecture stage in Frankfort, Pennsylvania that he met his end, age 68, felled by a stroke. He had delivered over 9600 lectures to some 9 million people.

Though I could say much more on the subject of John Bartholomew Gough, I will leave the last word to the man himself, with Helen Potter's help. Potter heard Gough speak many times and made careful notes of his delivery. This is from a speech given in the late 1870's and annotated by Potter. He's pretty dang funny. I won't toast you, Gough, but I will miss our time together.

John B. Gough Returns to Port: A Temperance Blog Part III (Originally published July 5, 2024)

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

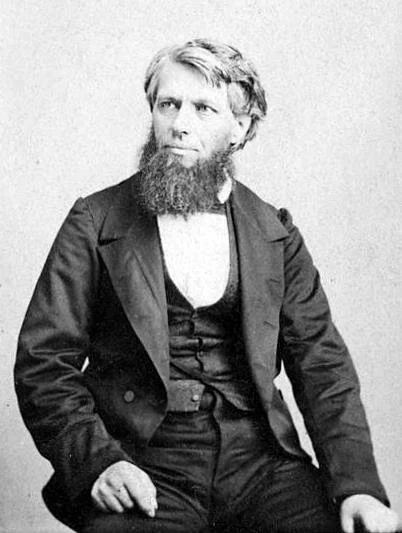

John Bartholomew Gough (1817-1886), in (even) later years.

If you missed it, read John B. Gough Part I here and Part II here.

First of all, a correction. The W.T.A.S was not, as I had assumed in the last newsletter, the WOMEN's Temperance Society (though there was one of these also in Newburyport), but the WASHINTONIAN Total Abstinence Society. More on that in a moment.

Next, a confession. I was in New York this weekend, and after imbibing the best Manhattan in Manhattan followed by a VERY old fashioned Old Fashioned, I felt a certain kinship with John B. Gough. New York City had been his home, after all, before Newburyport, before the wife and child and the temperance pledge and the lecture circuit. I can imagine the pull of the dark alleys of lower Manhattan. I was not on the wagon, clearly, but if I had been, a seat in a worn-down tavern might have tempted me away.

But before John B. Gough could belly up to a Bowery bar, he went for a visit back up to Newburyport.

On May 4, Gough was the opening act for Daniel Kimball in Newburyport. This advertisement ran on May 2.

When last we left our dubious hero, actor, bookbinder, and erstwhile pyrotechnician John B. Gough had taken the temperance pledge, promising to eschew drink, and while relating his tale of woe and degradation, had found the audience moved to tears. A career on stage had long been Gough's goal, and, despite a tipsy trip back to Newburyport and a bender in Boston in March, 1843, Gough seems to been on the straight and narrow, his star on the rise in the popular (and lucrative) temperance speaker circuit.

On May 2, 1845, the Washingtonian Total Abstinence Society (W.T.A.S.) announced a lecture in Newburyport’s Market Hall (where the Firehouse Center for the Arts is today) featuring Daniel Kimball, editor of the Temperance Standard, a Boston newspaper. The Washingtonians were the hottest new development in the temperance world, and their emphasis on the individual "drunkard", in the parlance of the time, suited the stage perfectly. Founded in 1840 in Baltimore, the Washingtonian movement promoted total abstinence, with members relying on sharing their experiences in a mutually supportive environment. Most other temperance organizations of the time focused on larger social and political change, seeing the individual as helpless victim of a societal problem. The Washingtonians, at least in the early years, followed roughly the same format as today's Alcoholics Anonymous, summoning the power of a supportive community to help members abstain completely from alcohol. Because of the element of the individual, supported by sociability, the W.T.A.S. was instrumental in launching the careers of various temperance speakers who, like Gough, relied on the strength of their personal testimony, rather than professional credentials. Along with the doctors, scientists, and politicians that tended to headline the meetings of other temperance societies, the Washingtonians loved a good personal narrative.

And so John B. Gough was invited to open the May 4 meeting of the W.T.A.S. with his unique combination of pathos, humor, and song. It seems to have gone over well, and Gough decided to spend a day seeing some old friends in town. He would return to Boston by train on May 6.

The first sign that something had gone awry appeared on May 10 in the Newburyport Daily Herald. Under the shipping news appeared a public notice from John B. Gough, and below that, another from Jacob Isaac Danforth.

These two notices appeared on May 10 in the Newburyport Herald.

John B. Gough, who had spent his dissipated youth in Newburyport, does not seem to have found the warm welcome he had expected during his brief return. He found himself first accused of failing to pay his debts, and so, to salvage his reputation, Gough announced that he would return to Newburyport to settle up with anyone who could prove a claim against him.

And then, twenty-four-year-old Jacob Isaac Danforth, who was helping his father Rufus at his Washington Street restaurant next to the train station, served John B. Gough a drink (or two, or three), and told a friend, who told a friend.

This 1851 map shows the location of Rufus Danforth's restaurant (R. Danforth, map center, next to the tracks), where his son Jacob was working on May 6.

John B. Gough, whose livelihood depended on not touching the stuff, caught wind of the rumors flying around Newburyport that he had been drinking. These stories were credible, to be fair. He had come to Newburyport two years before to lecture on temperance, having just come off a brandy and oyster bender in Boston, and seems to have rambled incoherently.

Gough marshalled support from the legal team of Dexter Dana of Newburyport and John Ross of Boston, and the trio showed up at the Danforth establishment with a Gough look-alike, asked Danforth if this was the man he had served, and when he hemmed and hawed and then said yes, they revealed their ruse and threatened to sue him for libel unless he immediately printed an apology and swore that he had not seen Gough at his bar.

Danforth, who clearly felt threatened and lacked the resources to fight such a suit, signed the apology, and the resulting retraction was printed in the newspaper on May 9, 1845 and then, in more detail, on the 10.

And then Gough got greedy.

Gough and his team told Danforth that despite his retraction, he would be paying $50 for Gough's legal bills, which would increase by the day if he did not pay up. Danforth, who had already admitted his alleged misidentification, paid the $50. Then, he sat down and wrote his own letter, two pages in all, to the paper.

Jacob Isaac Danforth was listed as a confectioner on Middle Street in the 1849 Newburyport City Directory, while his father is listed as a "restorator (restauranteur)" on Washington and Winter Streets.

"I now ask again, did Mr. Dexter Dana tell me the true purpose for which he wanted my signature, or did he want to make it appear, to operate against me as a liable against Mr. Gough in order to extort for me the sum of $50?... I now leave the matter with a candid public to draw their own conclusions of the actors who performed each his part in this affair."

Poor Jacob Danforth, confectioner, known for his pillowy-soft wedding cakes and his tasty taffy, was out $50 for good. Letters to the paper followed on both sides of the argument, but for the most part, the matter drew to a close.

And then, on September 13, with a certain amount of glee, the Newburyport newspaper carried an article from the New York Express. John B. Gough had vanished.

This notice from the New York Express was republished in the Newburyport Herald and offers a wonderful description of John B. Gough in 1845. He has "long, straight black hair, dark complexion, sharp features...," and was heavily accessorized in gold and carrying a small fortune in cash and gold.

Gough arrived in New York City on September 5, checked into his hotel, dropped his bags, and, nattily attired and flush with cash, went out on the town. It was nearly a week before his wife (he had remarried late in 1843) reported him missing. The disappearance of Gough was national news, another bit of publicity that ultimately made him a household name.

Well, gentle reader, this is embarrassing. We have barely arrived in New York City, and I have come to the end of my allotted space in this fine publication. I fear the many adventures of John Bartholomew Gough will require a Part IV. It's worth it, I promise.

John B Gough and the Joppa Gal: A Temperance Blog Part II (originally published June 21, 2024)

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

John Bartholomew Gough (1817-1886), in later years.

If you missed it, read John B. Gough Part I here.

This happens to me all the time, dear reader. I am introduced to a fascinating character who once graced the mean streets of Newbury(port), and I become immediately taken with their story. As I write about them, I do more research, and I find more things, and suddenly this blog is thousands of words long and I despair.

And then, voila, a solution. I will write a series! But life, and work, come at me sideways and I am distracted (or making sure you know all about the Garden Tour), or another article is more timely, and so I wander off the path only to discover, months later, that I have left some readers hanging.

Popular images such as this 1832 lithograph promoted temperance long before John B. Gough found his calling on its stage. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Gosh, I love thinking of you sitting around waiting to hear more about John B. Gough, because it made me return to this story, which returns to me with the ease of a visit with a high school chum. So let us pick back up where we left off.

When last we left our dubious hero, actor, bookbinder, and erstwhile accordion player John B. Gough had followed the Bunker Hill Diorama to Worcester. It was there on May 20, 1842, that he lost his "Joppa gal", 21-year-old Mary Cheney, and his infant daughter, Mary Jane. According to his enthusiastic biographer, the death of his family led to a new low for John B. Gough. He attended a church revival meeting and clumsily (and, I admit, a little hilariously) tried to steal the collection with a spittoon.

“Amid a fusillade of glorys, hallelujahs, and amens, the tipsy actor seized a huge, square, wooden spittoon, filled with sawdust, quids of tobacco, and refuse, and passing down the aisle, said: "We will now take a contribution for the purchase of ascension robes."

He was ejected, arrested, bailed, and turned to singing dirty songs in dirtier pubs for drinking money, and as summer turned to fall and Gough faced a long New England winter homeless, with “no flannels, no woolen socks, and no coats”. Destitute and despondent, he drank everything he had, bought a bottle of laudanum (a mixture of alcohol and opium), and “proceeded to the railroad track, put the bottle to his lips, and was about to make an exit from life through the door of suicide”.

At the last moment, he failed to throw himself under the train as he had planned. A few days later, as he was wobbling down the street to “a rum-hole in Lincoln Square to get a dram”, a man tapped him on the shoulder.

Lincoln Square, Worcester, where Gough met the waiter who would change his life, c. 1852.

The man was Joel Stratton, and he was a waiter at the Temperance Hotel. He noted that Gough was drunk and invited him to a temperance meeting the following night. To make a very long story somewhat shorter, he went to the meeting, told his story to an appreciative audience, and signed the pledge to never drink again.

This sobriety pledge from the 1840's is likely similar to the one signed by Gough in 1842. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

How we understand what followed depends on what you think of John Bartholemew Gough. On the one hand, Gough the actor must have quickly noted the effects of his heart-rending tale on the audience, who proved willing to offer not only sympathy but food, clothes, and cash. On the other hand, Gough the hard drinker walked through the door looking for help. That his story struck a chord and led to wealth and fame beyond his wildest imaginings was a stroke of luck. Was he a desperate addict, a cynical opportunist, or both? Well, I can tell you one thing – John B. Gough knew a good thing when he saw it, and by December, 1842, an announcement in the Worcester Waterfall, a temperance newspaper, announced that he was available to lecture (for a fee), and was also selling subscriptions of the Waterfall on commission. Of course, his entire career now depended on not drinking, or at least keeping his drinking a secret.

The Massachusetts Cataract and Worcester County Waterfall was a short-lived temperance newspaper where Gough first announced his availability as a lecturer.

When the spring lecture season began, Gough set his sights on Newburyport, where he could return in triumph in his flashy new suit. By his own account, he made his way first to Boston, where he met with some chums for oysters and brandy and then went to his hotel to sleep it off. The next morning, he “started in the cars for Newburyport”. What exactly happened there is a mystery, though on March 20, a scandalized representative of the Women’s Temperance Society wrote to the newspaper to apologize for their speaker. “In all my experience and my knowledge of temperance lectures, I never saw one before who had the bold affrontery, the deliberate vulgarity, the cold impedance, to get up before respectable audience like that convenient in Phoenix Hall, and pour out such a heterogeneous mass of unmeaning, unintelligible sentences without the least connection and without point, and which could be understood only by those were in the habit of visiting those miserable abode of vice and infamy when the language used can only be equal by the vices which engender them.” Was this Gough, still in his cups? It seems likely, given his next move. Gough, humiliated, his blossoming career in jeopardy, returned to Worcester and did the only thing he could do – he confessed that he had fallen off the wagon, blaming some medicine given to him by a doctor for a headache. To his surprise, after tearfully pledging that he would “rise up and combat King Alcohol”, he found himself not shunned, but exalted by his audience, whose attendance, and donations, at his events only grew.

"King Alcohol", which Gough swore to "combat", was a common image in temperance literature. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

On May 2, 1845, the Women’s Temperance Society announced a lecture in Newburyport’s Market Hall (where the Firehouse Center for the Arts is today) featuring Daniel Kimball, editor of the Temperance Standard, a Boston newspaper. The events of two years earlier a distant memory, the redeemed Gough was invited to open the May 4 event with his unique combination of pathos, humor, and song. Though his performance that evening was generally well received, some Newburyporters had a bone to pick with John B. Gough, who had pilfered their wares, run off with their women, and, perhaps most egregiously, failed to pay his debts. And when, on May 6, he passed the time while waiting for his train bellied up to the bar at Jacob Danforth’s establishment, Newburyporters had a thing or two to say about it.

You see, I did it again, gentle reader! Stay tuned for Part III as John Bartholomew Gough dabbles in extortion, visits a phantom soda fountain, and wakes up in a brothel.

John B Gough and the Joppa Gal: A Temperance Blog (originally published April 26, 2024)

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

Scott Nason is infuriatingly fascinating. If you have never had the good luck to meet Scott Nason, he is a walking treasure trove of information about this community, past and present. He has worked on Newbury(port) boats, bought and sold Newbury(port) antiques, and lived many other lives here that he tells me about in dribs and drabs with a wry smile. Ask him about the Joppa nicknames sometime.

I am regularly in the middle of some mundane but necessary task when Scott comes in and I ask him a question and then I find myself hours deep into some crazy story that has entirely, deliciously derailed my day.

Here's how it happened today: Scott came into the museum office to sign some paperwork. I asked him if he had an image of a Temperance Spa that once graced the corner of Middle and State Streets. That corner of the street is out of frame to the left in the image below, but you can just see a sign offering Hot and Cold Temperance Drinks, as the A.W. Thompson Oyster and Eating Room, later the decidedly non-temperance Grog, beckons from just beyond.

"Well", he says, "there was a famous temperance guy, married a Joppa gal, name was Cough or something like that." And we're off.

It is nearly midnight as I write this. I am still in the office, the three David Wood tall clocks within earshot tolling the passing hours. I have been in thrall to John Bartholomew Gough for something like five hours now.

It started with the Joppa gal. A quick rummage through the vital records reveals Mary B. Cheney marrying John B. Clough in 1838. She was 19 and he was 21. A detour into her ancestry links her to my family tree - her grandmother was a Sawyer - and so I plug her into the tree and she zips right up - my 5th cousin. Her father, Samuel Sawyer, drowned in a December fishing accident when she was 15, and the news was reported in New York City.

Meanwhile, in New York City, John Bartholemew Gough was having a very bad time indeed. Gough was born into a poor but respectable family in England and educated by his mother, a seamstress. When he was twelve, his father died, and he was sent to the United States to find work. After two years upstate, he returned to New York City and went to work as a book binder. His mother and sister joined him when he was sixteen. It was a hard life - they were very poor, but Gough later recalled his short time with his mother in New York with great fondness.

Jane (Gilbert) Gough, John's mother, died of a stroke in June 1834. John recalled holding her hand all night as she lay on their kitchen floor before the undertaker came for her body. She was buried in a pauper's grave. John B Gough, bereft, began to drink and, emboldened by the drink, he began to contemplate a career as an actor. It was his acting, not his book-binding that propelled him out of the big city, and landed him, through many twists and turns, in Newburyport, in the arms of a Joppa gal.

The Lion Theatre was built in 1836, and was later re-opened as the Bijou. Private collection.

It was to the newly built Lion Theater that Gough went. His first appearance in Boston was, ironically, a satirical play lampooning the "prominent temperance men" of Boston. And then, as is the way, the play closed, and Gough was once again thrown out of work.

After several failed attempts at regular employment, when all seemed hopeless, in a "destitute situation", Gough heard that a man in Newburyport was looking to hire a book-binder. Gough, "travelling partly by stage and partly by (railroad) cars" entered Newburyport late in the evening of January 30, 1838 and began work the next morning.

1838 was an interesting time to be a poor man in search of hard liquor. Just three days before Gough's arrival, Massachusetts had passed a law banning the sale of spirits in quantities of less than 15 gallons. This led, not to a reduction of the drinking of aforementioned liquor, but to a precipitous rise in cooperative drinking. Men (and women) would pool their money, buy 15 gallons of rum or gin, and go on a bender. Whole shops and whole ships were emptied out for days at a time. Individual towns also had the right to issue licenses for liquor for medicinal purposes, which they handed out liberally in port towns like Newburyport.

It did not take long for Gough to find himself part of a Newburyport drinking club. He joined a fire-engine company, and before long, was once again on the "high road to dissipation" and irregular employment. He joined a fishing crew, drank quantities of rum whenever he went on shore or encountered another vessel, and having met, wooed, and possibly impregnated the lovely Mary Cheney of Joppa (there are some indications that a child was born and died in 1839), he married her on November 1, 1838.

And then in March, 1839, with a wife to support, he thought he would give performing another go, this time with an accordion in Amesbury. Gough, billing himself as "the celebrated singer from New York and Boston Theatres", which was only partially untrue, was still drinking in quantity, and his performance was not the breakout event he had hoped for.

And so, Gough went back out to sea, this time a short- six-week stint to the Bay of Fundy with his brother-in-law, John Clark Cheney, and was then unemployed once again. It was a harsh existence, despite the support of his wife and her family. Gough tried to go into business for himself, but was swindled by a "Newburyport rum-seller" who rented him stolen tools. It was all repossessed, and Gough, sending his wife to stay with his sister in Rhode Island, went on such a bender he began to hallucinate and a doctor was called.

Mary returned, Gough sobered up for a short while and then the theater came to town once again.

The Bunker Hill Diorama came to Newburyport in 1841 amid the national push to complete the construction of the Bunker Hill Monument. Gough was hired to do some "comic singing" and as a general assistant to the production, turning the cranks that marched the model soldiers up Bunker Hill.

When the Diorama left Newburyport, Gough went with it, sending his wife back to stay with his sister. The show spent three months in Lowell, where "rum claimed nearly all my attention", and then moved on to Worcester. Gough was responsible for basic pyrotechnics as part of the show, which he hated, "half-suffocated with smoke, blackened with the (gun)powder, sometimes fingers burned, or hair and eyebrows singed".

Things went from bad to worse in Worcester. Gough's hands were too shaky to turn the crank. He was clumsy and careless, and audiences hissed and threw things at him. Determined once again to sober up, Gough sent for his wife, installed her in a tenement, and secured a steady job, having his employer pay his board and tobacco so he would not have money for alcohol.

Mary was pregnant and increasingly unwell through the cold winter and early spring of 1842. Despite having no access to cash, Gough began to drink again, asking for medicine at the pharmacy, selling their furniture and other possessions.

When Mary Cheney Gough went into labor on May 11, the women attending her told Gough to get two pints of rum to ease her pains and, one may assume, for their use as well. He drank most of it, and so, nine days later on May 20, when Mary Cheney Gough of Newburyport, and their infant daughter, Mary Jane, both died, John B. Gough was, by some accounts, passed out on the floor.

The Worcester death record reads, Mrs. Mary B. Gough, wife of John B Gough, died May 20, 1842, aged 22 years - Puerperal fever. Mary Jane Gough, child of above, died same day, aged 9 days.

It was the death of John B Gough's Joppa gal that led to a bender so severe that Gough tried to drink laudanum and throw himself under a train. And it was this bender that led him to take a kindly Quaker up on his offer to take the temperance pledge, and it was this pledge that led him to a life as the best-known temperance speaker of his time.