Newburyport's Albert Pike Toppled, Part Two

To read more about Albert Pike’s early life in Newburyport, click here.

It’s almost too easy. Albert Pike, former Newburyport school teacher, enslaver, racist, secessionist, is not a complicated research subject. My feelings about him are equally uncomplicated. At every turn, when he had a chance to express his support of slavery, spew racist hatred, or feed his baser appetites, he did so publicly, and with gusto. The frightening thing about Albert Pike, to me, is how many people excused away the ugliness that came from his own mouth, and his pen.

In 1891, as Pike lay dying in Washington, D.C., the Newburyport Daily News called him “a venerable author and statesman”. Later contributors to the Daily News would describe him as a kindly enslaver (check that with the people who ran away from bondage in his Arkansas home), and a lukewarm secessionist who only joined the Confederacy to protect his property.

“HEY”, I find myself yelling at my computer screen. “This guy LITERALLY WROTE THE CONFEDERATE WAR SONG.” That’s right. Albert Pike wrote the lyrics to Dixie. Specifically, he wrote these stirring lines:

Southrons, hear your country call you!

Up, lest worse than death befall you!

To arms! To arms! To arms, in Dixie!

Apparently, the preservation of the Union and the eventual end of slavery was…worse than death. Not very ambiguous.

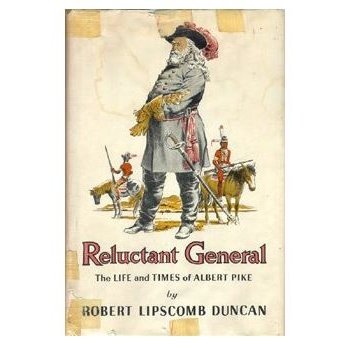

And, lest you think this version of the popular minstrel song fell into obscurity after the war, it was Albert Pike’s lyrics that became a hit once again 100 years later when Tennessee Ernie Ford recorded Dixie for Capitol Records in 1961. Oh, and also in 1961, Albert Pike was reimagined as the “Reluctant General” for a children’s book.

Let’s just say, Albert Pike could have written the best-selling pamphlet, “Why I Love Slavery and the Confederacy and the KKK”, and thousands of people would still say, essentially, “there’s no way to know what he was REALLY like.” But I digress. Back to the narrative.

On November 22, 1861, former Byfield resident and Newburyport schoolteacher Albert Pike joined the Confederate Army as a brigadier general. He had already been working hard for the Confederate government, however, as his previous experience with Native American legal issues had resulted in his role as Confederate Commissioner to the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole, who had been promised their own free state at the successful end of the war. They had also been promised that they would only be called on to fight in the defense of Indian Territory. And so, after much negotiation – the Cherokee in particular were understandably skeptical about the arrangement – Pike was placed in charge of training three regiments of cavalry. He led two of these regiments into the disastrous Battle of Pea Ridge on March 7, 1862 near Fayetteville, Arkansas, a violation of the defense-only agreement in their treaty, which, to his credit, he protested. Once on the battlefield, well, I’ll let an eyewitness take it from here.

“On the morning of the 7th of March I was on the battlefield of Pea Ridge. While my command was engaging the enemy near Leetown, I saw in the rebel army a large number of Indians, estimated by me at one thousand. After the battle I attended in person to the burial of the dead of my command. Of twenty-five men killed on the field of my regiment, eight were scalped, and the bodies of others were horribly mutilated, being fired into with musket balls and pierced through the body and neck with long knives. These atrocities I believe to have been committed by Indians belonging to the rebel army. "

- Cyrus Bussey, Colonel, 3rd Iowa Cavalry

This flag, the only known example of a Confederate American Indian regimental flag, is owned by the National Park Service and is associated with one of the regiments at Pea Ridge.

How involved Albert Pike was with the atrocities committed at Pea Ridge is a matter of considerable debate. Suffice it to say, it made Pike one of the most hated men in the North and a pariah in the Confederacy as well. Later, Pike denied that he had any role in the behavior of the troops under his command, claiming that he was “angry and disgusted” with the whole affair. His hometown newspaper tells a different story entirely. In May, two months after Pea Ridge, and after widespread reporting on the atrocities, the front page of the Newburyport Daily Herald noted that Pike praised his troops for “gallantry”. It does rather upend his case for plausible deniability.

The Boston Evening Transcript wrote a scathing article about the episode, concluding that “renegades are always loathsome creatures, and it is not to be presumed that a more venomous reptile than Albert Pike ever crawled upon the face of the earth…there is no pit of infamy too deep for him to fill”.

While Pike was being excoriated in the Northern press, his relationship with his fellow Confederates deteriorated as well. Pike was ordered by Gen. Thomas C. Hindman to turn over funds. Pike refused and issued angry missives against his commanding officers before hiding out in the hills of Arkansas. He was charged with stealing money and material and arrested for insubordination and treason. He was released from a Texas prison in 1863, having resigned from his command. Col. Douglas Cooper remarked to President Jefferson Davis that Pike was "either insane or untrue to the South."

Pike rode out the war in Arkansas, eventually becoming an associate justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court as the Confederacy disintegrated. Pike, considered a traitor in the South and a butcher (and also a traitor) in the North, saw his property confiscated and fled first to New York and then to Canada where he petitioned, and received, a pardon from Andrew Johnson in 1866. Upon his return to Arkansas, however, he was charged with treason, though the charges didn’t stick. He fled again, this time to Memphis, Tennessee, and then to Washington, D.C. His wife, Mary Ann, remained in Little Rock, and Pike began a very public affair with the ambitious 19-year-old sculptor Vinnie Ream, forty years his junior.

Albert Pike Klan chapters sprang up in Illinois, Kansas City, Oklahoma, Virginia, and New Jersey in the early 20th century.

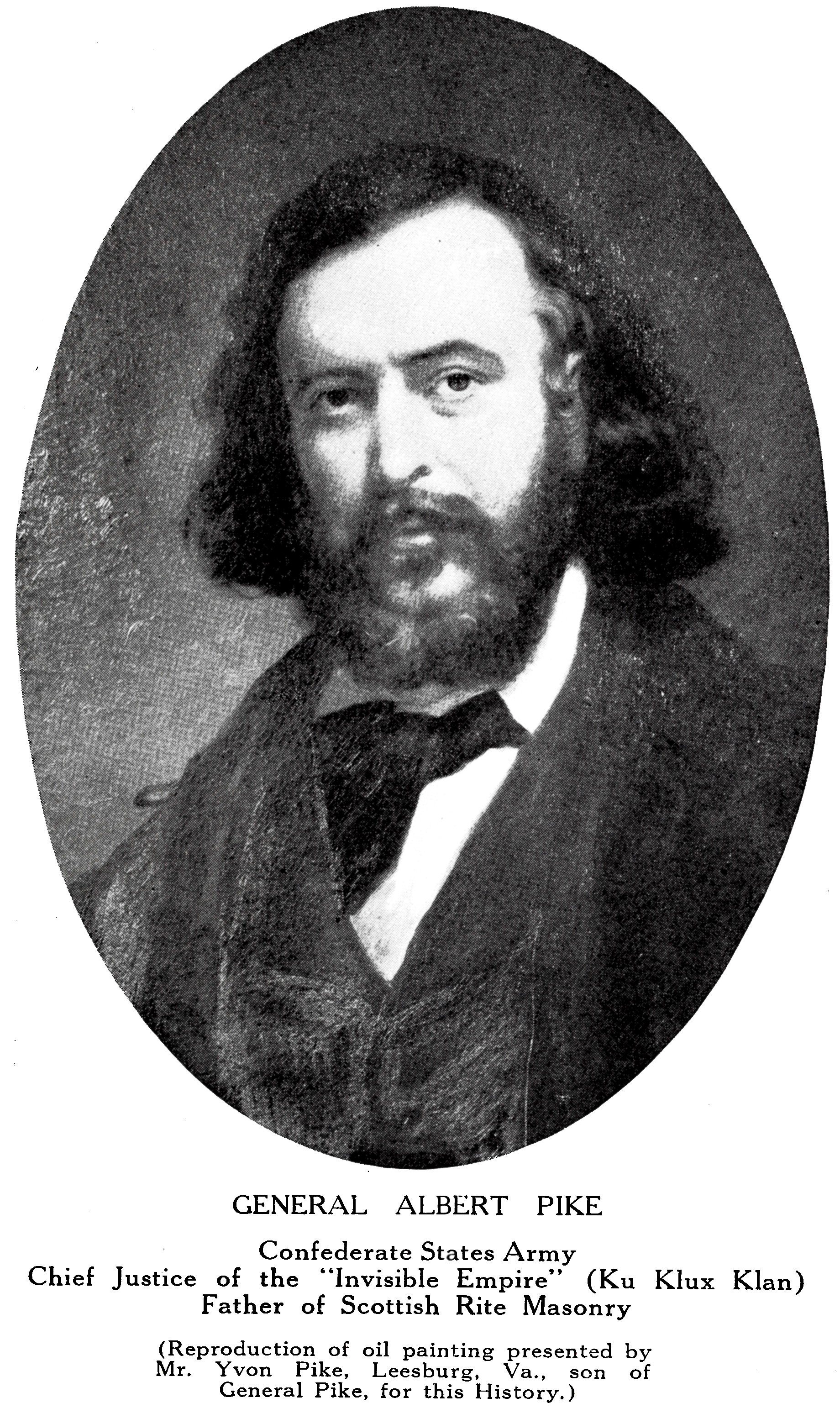

But let’s go back to Tennessee. There is ample evidence that Albert Pike was instrumental in forming the Ku Klux Klan, established in 1865 in Tennessee and organized in 1867 under the leadership of former Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest. Though early Klan membership remains largely secret, Pike published editorials essentially arguing for an expansion of the Klan. "If it were in our power, if it could be effected, we would unite every white man in the South, who is opposed to negro suffrage, into one great Order of Southern Brotherhood, with an organization complete, active, vigorous, in which a few should execute the concentrated will of all, and whose very existence should be concealed from all but its members.” Early, laudatory Klan histories published in the early 20th century praised Pike’s role as a high-ranking founding officer, appointed by Forrest himself as the Klan’s “chief judicial officer”, and a “grand dragon”. A cursory newspaper search turns up Albert Pike Klan chapters across the country by the 1920’s.

In a 1905 history of the Ku Klux Klan, Susan Lawrence Davis, daughter of a founding member, reprints a portrait of Pike that she uses with permission of Pike’s son. It seems unlikely that such permission would have been granted unless the family fully embraced his Klan leadership.

Much has been written about Albert Pike’s Masonic leadership, enough, in fact, that I will give it short shrift here. Pike had been involved in Freemasonry since the 1840’s, becoming Sovereign Grand Commander of the Scottish Rite's Southern Jurisdiction in 1859. He spent much of his later life working on the rituals of the Scottish Rite, publishing Morals and Dogma of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry in 1871.

Albert Pike died of esophageal cancer on April 2, 1891, at the Scottish Rite Temple in Washington DC. His remains were interred there in 1944, long after the ugly, bloody work of Albert Pike had been sanitized, excused, and explained away by generations of apologists. Still, today, his name is everywhere. North of Langley, Arkansas, the Albert Pike recreation area boasts “picnic tables, toilets, drinking water, and parking”.

A 1922 traveler on the Albert Pike Highway could stop at the Albert Pike Café. The highway wound through the Ozarks from Hot Springs, Arkansas to Colorado Springs, Co.

A 1922 traveler on the Albert Pike Highway could stop at the Albert Pike Café. The highway wound through the Ozarks from Hot Springs, Arkansas to Colorado Springs, Co.

Readers of the first installment of this series (we love your emails!) found Albert Pike Road, Albert Pike Apartments, and, perhaps unsurprisingly, the Albert Pike Memorial Temple, listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

At the close of Albert Pike’s memorial service, its details printed in the Evening Star, Washington D.C. edition, the following words were read:

“Who will be man’s accuser?”

“His conscience.”

“Who his defender?”

“No one.”

“Who will give testimony against him?”

“No one.”

We beg to differ.

Join us for Part III of Albert Pike Toppled, where we explore the curious transformation of Albert Pike from Confederate traitor to peace-loving hero and revered son of Newburyport (and Byfield).